ATSC 113 Weather for Sailing, Flying & Snow Sports

Cold Fronts

Learning Goal 5g. List the weather conditions associated with a cold front and their relevance to snow sports.

Background information on cold fronts is covered in detail in the Flying Learning Goal 3h. To remind you, a cold front indicates the boundary between relatively warmer and colder air masses, where the colder air is advancing.

Much of the hazardous sensible weather we experience (snow, winds, fog), as well as changes in this sensible weather, are associated with cold fronts. How is the weather associated with cold fronts relevant to snowsports? How do we identify this weather and predict its occurrence?

Temperature trends

Not only do temperatures decrease (become colder) the higher up a mountain you go, but temperatures also become colder with time behind a cold front, where there is a colder air mass. I have seen temperatures as low as -25°C on Whistler Mountain. At these temperatures, especially with high winds that cause wind chill (see below), frostbite and hypothermia are genuine concerns and you need to be wearing the appropriate gear, covering as much skin as possible (Fig. 5g.1).

Fig. 5g.1 These skiers are well prepared for cold temperatures and strong winds in the wake of a cold front on Mount Hood, OR, USA. (Credit: West)

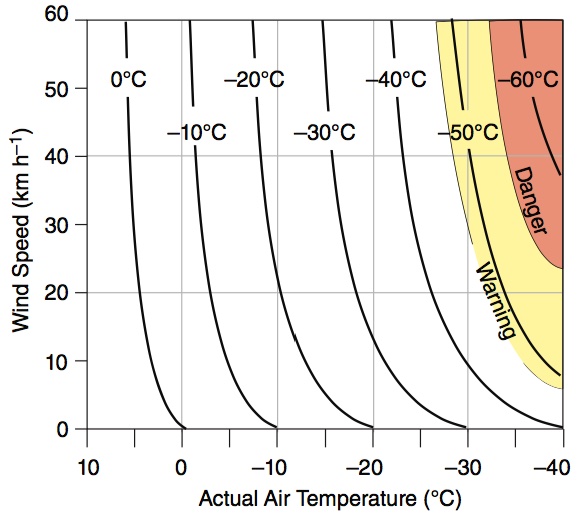

The wind chill is not the actual temperature, but rather the apparent temperature, or how cold it feels to a human due to the combined affects of temperature and wind. The harder the wind blows, the faster heat is removed from the human body. At a wind chill below 0°C you risk discomfort, and over a long period of time, if not properly dressed, hypothermia. Below -10°C you may suffer frostbite and hypothermia after a short amount of time (again, if not properly dressed). For wind chill values below -55°C, skin can freeze in just two minutes! The wind chill formula was developed as a joint effort by the US and Canada, in part by using volunteers in a refrigerated wind tunnel. You can check out the wind chill chart below. Wind chill is particularly a concern on ridgetops (where it's windier), during arctic air outbreaks at the coast (Learning Goal 6l), and in regions where very cold arctic air is more common, like the Canadian Rockies.

Fig. 5g.2. Wind chill. Start with the actual air temperature on the bottom axis, move straight up until you get to the wind speed. The curved line that passes through that point is the wind chill. If your point is between two curved lines, then interpolate (estimate the in-between value based on how close it is to the curved lines). Example, if the actual air temperature is -20 degC, and the wind speed is 40 km/hour, then the wind chill is about -36 degC. (Credit: Stull)

Winds

Winds are typically stronger in the vicinity of fronts. Cold fronts generally bring stronger and gustier winds than warm fronts. The location of the strongest winds relative to the cold front varies storm to storm. Learning Goal 5j will teach you about predicting high winds. Also, as is discussed in Learning Goal 5f, wind direction typically shifts with the passage of a front.

Precipitation

Don't forget that fronts are three-dimensional. The denser, colder air behind the front undercuts the warmer air ahead of it as it moves forward, causing that warmer air to rise up, cool, condense, often forming tall cumulonimbus clouds (Learning Goal 1a), sometimes filling the depth of the entire troposphere.

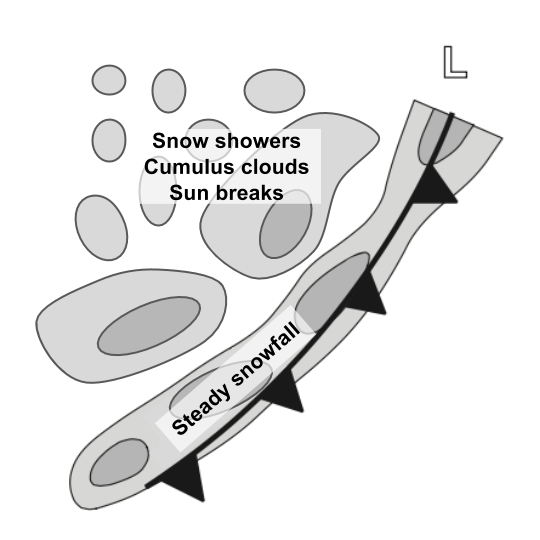

As a result, cold fronts generally bring a narrow (relative to the length of the front) band of organized precipitation along the frontal zone. The band can be 10-100 km wide (Fig. 5g.3). This typically brings with it a period of steady moderate or heavy snowfall. Strong cold fronts in the spring may be accompanied by thunderstorms (even thundersnow!).

Fig. 5g.3 Typical clouds and precipitation associated with a cold front. Strong vertical motion at the front causes clouds and precipitation. (Credit: Stull/West)

In winter and at higher elevations in the mountains, cold fronts generally bring precipitation in the form of snow, and sometimes graupel and ice pellets (see Learning Goal 7k). Rain or mixed rain and snow can occur if temperatures are warm enough. In warmer storms, or warmer (lower) elevations, cold frontal precipitation may start as rain, and transition to snow as the temperature drops behind the front. While cold fronts themselves may be accompanied by hazardous weather for snow sports enthusiasts, the snow that accumulates on the ground during their passing makes for great skiing. Often the best skiing comes in the hours following a cold front passage, as the skies tend to clear somewhat. We'll talk about determining the rain/snow line in Learning Goal 7a.

Visibility

This may sound obvious, but it really helps if you can see where you are going while skiing or snowboarding. This is far more important when you are skiing in the backcountry, i.e. not in a resort. Resorts have markers, signs, and ropes at the ski area boundaries, and even then it is possible to go a different way than you intended. However, you will likely always remain in a safe and patrolled area, even if you lose your friends. This is not the case when skiing in the backcountry, where you and your crew are the wayfinders and there are no boundary ropes, no "cliff" warning signs, and definitely no ski patrol.

Visibility on mountain slopes can be reduced due to a number of factors associated with cold fronts, some which we have already talked about:

Heavy snowfall

- Heavy precipitation in the form of snowfall can reduce visibility down to tens of metres or less for sustained periods of time. This can happen both with the cold frontal snowfall, as well as for more brief periods of time in the showers in the postfrontal airmass.

Fig. 5g.4 Heavy snowfall causing limited visilibity and drooling. Falls Lake, Coquihalla, BC. (Credit: West).

Blowing snow

- Blowing snow can be snow that's falling and blowing, or snow that's been lifted up from the ground. It only takes a 14 km/h wind to pick up snow off the ground and start moving it around. Blowing snow can be continuous, or, in gusty conditions, vary a great deal from one moment to the next. When the wind is strong, visibility may be limited to a few metres. Perhaps more importantly, visibility is zero when your eyes are closed! Which they may have to be if you're not properly equipped with goggles.

Storytime

I was in a situation in the Blackcomb backcountry that seemed nearly unsurvivable. The wind was blowing hard, there was drifting snow making it nearly impossible to open my eyes. I couldn't see to move forward, frostbite seemed imminent. A friend calmed me down, and told me to put on my goggles and balaclava. These are essential items that should always go in your backcountry pack. They're also recommended for resort skiing if the weather is less than ideal. Just like that, the situation became manageable, and we continued with our ski day, moving to a less windy location.

Clouds and fog

- In general, clouds block visibility. This could be vertical visibility (can only see uphill to the cloud base), or horizontal visibility (can't see route down or the next peak over if a cloud is blocking your view).

Fig. 5g.5 - Standing in clear air, next to a cloud that's limiting horizontal visibility. Mount Rainier, WA, USA. (Credit: West)

An interesting aspect of being at the same elevation at which clouds frequently exist, is that sometimes you find yourself inside a cloud. Of course, when a cloud exists at ground level, we typically refer to it as fog . In mountains you can call it either. This typically limits your visibility severely, and it can even limit your ability to see the ground at your feet. This is known as a whiteout since all you can see is a kind of white in every direction (fog in the air and snow on the ground) (Figs. 5g.6 and 5g.7).

I've had friends navigating in the backcountry, worried about walking off a corniced cliff, that repeatedly throw their ski pole a few feet in front of them just to give some definition to the ground in front of them.

Fig. 5g.6 - Whiteout conditions, inside of a cloud, at the top of Mount Garibaldi, BC. (Credit: West)

Fig. 5g.7 - Near-whiteout conditions on Mount Rainier WA, USA. (Credit: West)

In the wake of a cold front, after the main band of clouds/precipitation, there is typically a gradual drying trend. This leads to breaks in the (cumulus) clouds and precipitation. Convective showers are possible because the air mass is typically unstable due to cold air moving in aloft (Fig. 5g.8).

Fig. 5g.8 - A convective snow shower in the wake of a cold front. Visibility is improving, as the skies begin to clear and the sun comes and goes, but the snow shower still creates a short-term hazard with clouds/fog, intense but short-lived snow, and gusty winds. Hurley Silver Mine area, Duffey Road, BC. (Credit: West)

Since the instability is often driven by cold air moving in over a sun-heated ground, postfrontal clouds often dissipate in the evening as the heating source goes away, and the atmosphere stabilizes. Regardless, eventually drier air moves in, and the clouds dissipate.

Blizzard conditions

- During the passage of a cold front, it is not uncommon to experience everything discussed above while on a mountainside. With that combination, you have yourself some fierce blizzard conditions (Fig. 5g.9)! In this scenario, it may be more sensible to stay inbounds in a resort rather than venture into the backcountry, or head to the lodge until the worst is over. It is up to you to determine the intensity of the storm to make your decision.

Fig. 5g.9 - Skiers trudging through blizzard conditions in the Mount Baker backcountry, WA, USA. (Credit: West)

| Weather Element |

Canada |

USA |

|---|---|---|

| wind speed of at least |

40 km/hr |

35 mph (=56 km/hr) |

| visibility at or below |

400 m |

1/4 mile (= 400 m) |

| snow |

blowing and/or falling |

blowing and/or falling |

| duration of at least |

4 hours |

3 hours |

Key words: cold front, wind chill, isotherms,

frontal zone, wind barbs, fog, whiteout, frostbite, hypothermia,

blizzard

Figure Credits: Howard: Rosie Howard, West: Greg West, Stull: Roland Stull