Geologists find lost fragment of ancient continent in Canada’s North

Maya Kopylova, E Tso, F Ma, and D G Pearson

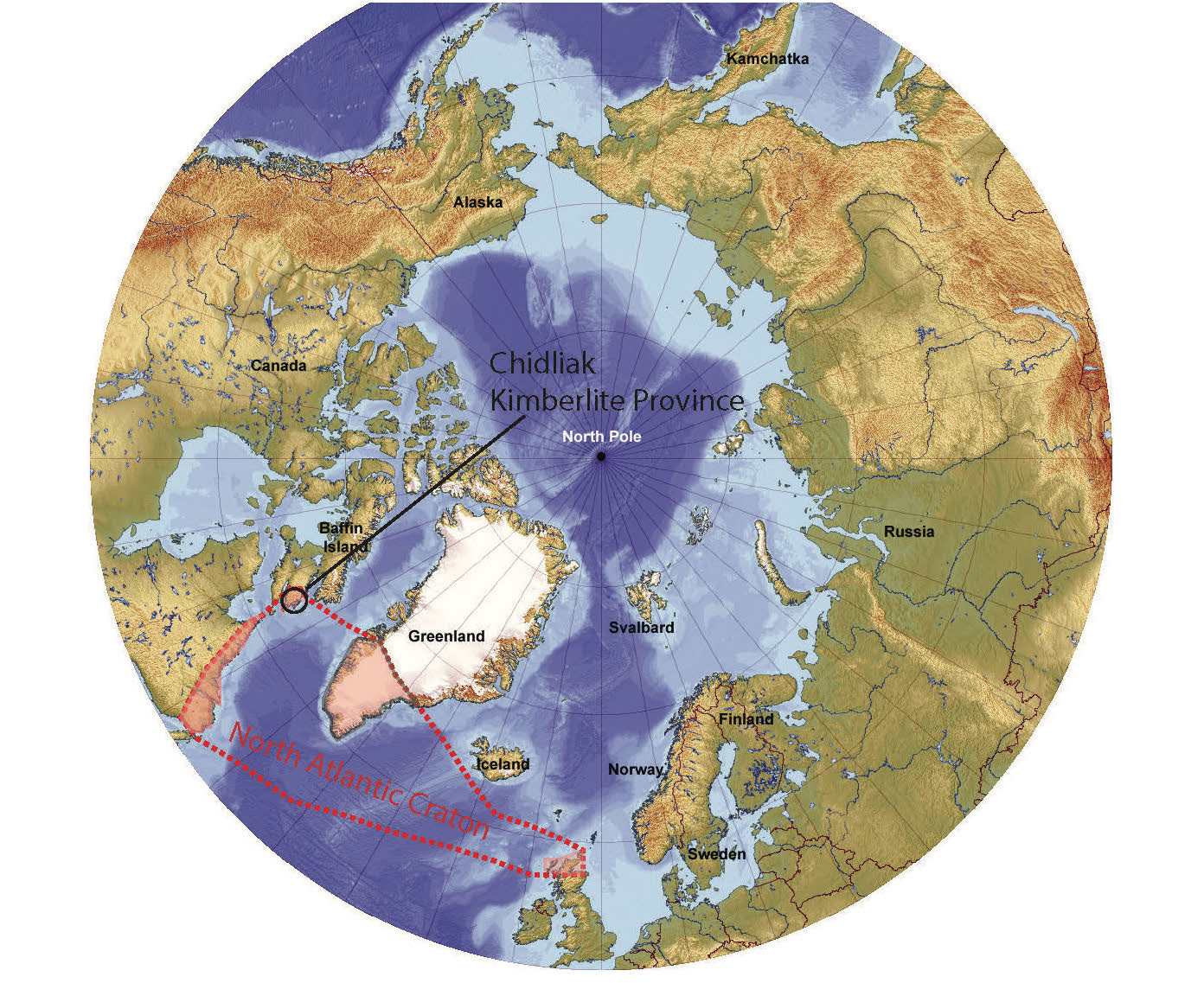

Sifting through diamond exploration samples from Baffin Island, Canadian scientists have identified a new remnant of the North Atlantic craton—an ancient part of Earth's continental crust.

A chance discovery by geologists poring over diamond exploration samples has led to a major scientific payoff.

Kimberlite rock samples are a mainstay of diamond exploration. Formed millions of years ago at depths of 150 to 400 kilometres, kimberlites are brought to the surface by geological and chemical forces. Sometimes, the igneous rocks carry diamonds embedded within them.

"With these samples we’re able to reconstruct the shapes of ancient continents based on deeper, mantle rocks.”

“For researchers, kimberlites are subterranean rockets that pick up passengers on their way to the surface,” explains University of British Columbia geologist Maya Kopylova. “The passengers are solid chunks of wall rocks that carry a wealth of details on conditions far beneath the surface of our planet over time.”

But when Kopylova and colleagues began analyzing samples from a De Beers Chidliak Kimberlite Province property in southern Baffin Island, it became clear the wall rocks were very special. They bore a mineral signature that matched other portions of the North Atlantic craton—an ancient part of Earth's continental crust that stretches from Scotland to Labrador.

“The mineral composition of other portions of the North Atlantic craton is so unique there was no mistaking it,” says Kopylova, lead author of a new paper in the Journal of Petrology that outlines the findings. “It was easy to tie the pieces together. Adjacent ancient cratons in Northern Canada—in Northern Quebec, Northern Ontario and in Nunavut—have completely different mineralogies.”

Cratons are billion-year old, stable fragments of continental crust—continental nuclei that anchor and gather other continental blocks around them. Some of these nuclei are still present at the center of existing continental plates like the North American plate, but other ancient continents have split into smaller fragments and been re-arranged by a long history of plate movements.

“Finding these 'lost' pieces is like finding a missing piece of a puzzle,” says Kopylova. “The scientific puzzle of the ancient Earth can’t be complete without all of the pieces.”

The continental plate of the North Atlantic craton rifted into fragments 150 million years ago, and currently stretches from northern Scotland, through the southern part of Greenland and continues southwest into Labrador.

The newly identified fragment covers the diamond bearing Chidliak kimberlite province in southern Baffin Island. It adds roughly 10 percent to the known expanse of the North Atlantic craton.

This is the first time geologists have been able to piece parts of the puzzle together at such depth—so called mantle correlation. Previous reconstructions of the size and location of Earth’s plates have been based on relatively shallow rock samples in the crust, formed at depths of one to 10 kilometres.

"With these samples we’re able to reconstruct the shapes of ancient continents based on deeper, mantle rocks,” says Kopylova. “We can now understand and map not only the uppermost skinny layer of Earth that makes up one percent of the planet’s volume, but our knowledge is literally and symbolically deeper. We can put together 200-kilometre deep fragments and contrast them based on the details of the deep mineralogy.”

The samples from the Chidliak Kimberlite Province in southern Baffin Island were initially provided by Peregrine Diamonds, a junior exploration company. Peregrine was acquired by the international diamond exploration company and retailer De Beers in 2018. The drill cores sample themselves are very valuable, and expensive to retrieve.

“Our partner companies demonstrate a lot of goodwill by providing research samples to UBC, which enables fundamental research and the training of many grad students,” says Kopylova. “In turn, UBC research provides the company with information about the deep diamondiferous mantle that is central to mapping the part of the craton with the higher changes to support a successful diamond mine.”