Thunderstorm Hazards > Convective Turbulence

Learning Goal 4c. Identify thunderstorm hazards to flight &

how to avoid them. Convective turbulence.

Thunderstorms are convective clouds, which means they are driven by the buoyancy of warm rising air inside the cloud. Turbulence is the name for random gusty fluctuations (vertical and horizontal) of the wind. Turbulence usually consists of a lot of different-sized swirls of air motion (called eddies) superimposed on each other.

Here we focus on one type of turbulence, convective

turbulence, which is associated with thunderstorms.

Unfortunately for us, the visual

appearance of a thunderstorm cloud (cumulonimbus)

is not always a good guide to its intensity. Namely, you cannot

know how dangerous a thunderstorm will be just by looking at it.

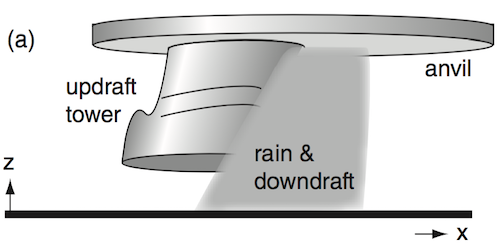

Thunderstorms have strong updrafts and downdrafts adjacent to each other, driven by buoyancy. These violent convective cells can extend throughout the whole depth of the thunderstorm (10-15 km deep), and can also have widths of 10-15 km (see thunderstorm sketch below). The strong vertical motions also create more random medium and smaller size eddies and turbulence, driven by the shear of the vertical velocity. (Shear refers to the change of updraft speed with horizontal distance.)

What if I fly into a thunderstorm cloud?

Your best course of action is to not fly into thunderstorm clouds at all. That being said, if you do accidentally fly into one...

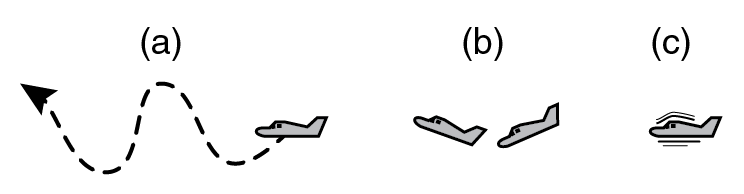

- The largest-size updrafts and downdrafts would move your whole aircraft upward or downward away from your assigned altitude (see figure A below).

- The medium-size eddies would cause intense and random rolling motions (the aircraft wings bank right and left), pitching motions (the aircraft nose is rocked up and down, see Figure B), and yawing motions (the aircraft nose is rocked left and right).

- The smaller eddies would cause violent shaking, similar to what you would feel in a car driving over a very bumpy road (see Figure C).

All of these motions would happen simultaneously, causing a very rough ride and making the aircraft very difficult to control.

For weaker turbulence in fair weather, the normal pilot reaction is to manipulate the steering wheel (called the control yoke or stick in an aircraft) to try to keep the aircraft level and at its assigned altitude. In severe or extreme convective turbulence, however, if you tried to keep the aircraft level, you would need to move the yoke so rapidly and violently that you could cause the aircraft to exceed its structural limits (i.e. cause things to break). So instead, the recommendation to pilots is to tolerate being occasionally temporarily out of control and off the assigned altitude, and instead make smaller control inputs (smaller movements of the yoke) to try to avoid over-stressing the aircraft.

To aid in minimizing this stress, each aircraft model has a recommended maneuvering speed, depending on aircraft loading (weight) and altitude. The maneuvering speed is slow enough that any violent control inputs (i.e. jerking on the steering wheel) by the pilot would cause the aircraft to stall (lose aerodynamic lift) and start to fall out of the sky, instead of having the wings break off. This is good, because while pilots can easily recover from stalls — all pilots learn stall-recovery techniques in basic flight training — there is no possible recovery if the aircraft wings break off! Pilots are trained on how to fly in light to moderate turbulence, and the aircraft operators manual lists the maneuvering speeds.

But again, your best course of action is to not fly into thunderstorm clouds or cumulus-congestus clouds at all, where you can expect the strongest turbulence.

Clear Air Turbulence (CAT) & Sucker Holes

Be wary, because severe turbulence can also happen in the clear air outside of, but adjacent to, the thunderstorm cloud. This is one type of Clear Air Turbulence (CAT). For example, both the USA and Canadian "Aeronautical Info Manual" (AIM, 2017) recommends that pilots get no closer than 20 nautical miles to any severe thunderstorm, including any thunderstorm with tops at 35,000 feet or higher.

Those references also recommend that if multiple thunderstorms or radar echoes are separated horizontally from each other by less than a certain amount (as of July 2015, USA: 20 to 30 miles; Canada 40 nautical miles), then the space between those storms is also likely severely turbulent. The sad fact is that inexperienced pilots trying to cross a line of thunderstorms can be lured toward a small but dangerous gap of clear air between thunderstorms (see figures below)—such gaps can have severe turbulence and can close-in on the aircraft. These gaps are nicknamed "sucker holes" because they lure unsuspecting pilots to their death.

- This video recreates a fatal accident when a pilot attempted to fly through a sucker hole. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=83uvKWJS2os

I encountered many lines of thunderstorms during my decades of flying light aircraft across North America. The planes I rented were small and slow. So if a thunderstorm line was in my path, I would find an airport before I got to the thunderstorms and get clearance to land, i.e. I would not fly into the thunderstorm. At the airport, I would either tie the airplane down or pay to have it towed into a hangar to protect it from possible hail. Only after the thunderstorm line passed over would I take off again and resume my flight to my destination.

Key words: buoyancy, clear air turbulence (CAT), cumulonimbus, eddies, maneuvering speed, turbulence, shear, stick, sucker holes, yoke

Image credits. All figures by Roland Stull, except the first thunderstorm photo, taken by Dr. Wolf Read (used with permission, image was flipped left-right).