ATSC 113 Weather for Sailing, Flying & Snow Sports

Local Tides and Currents

Learning Goal 10d: Describe the forces that drive tidal cycles and how tides relate to currents and sailing.

As a sailor, you won’t make it very far without knowing about your local tides and currents. Low tides can prevent you from getting in and out of a bay due to shallow water, while high tides can block you from travelling under bridges or hide rocks that are only visible at low tide. Tides will also help you to determine how much chain to put out when setting your anchor. The currents associated with tides can also speed or slow down your journey, depending on their strength and direction. Knowing what the tides are doing in the areas you are going to be sailing in will allow you to travel safely and efficiently.

Tide

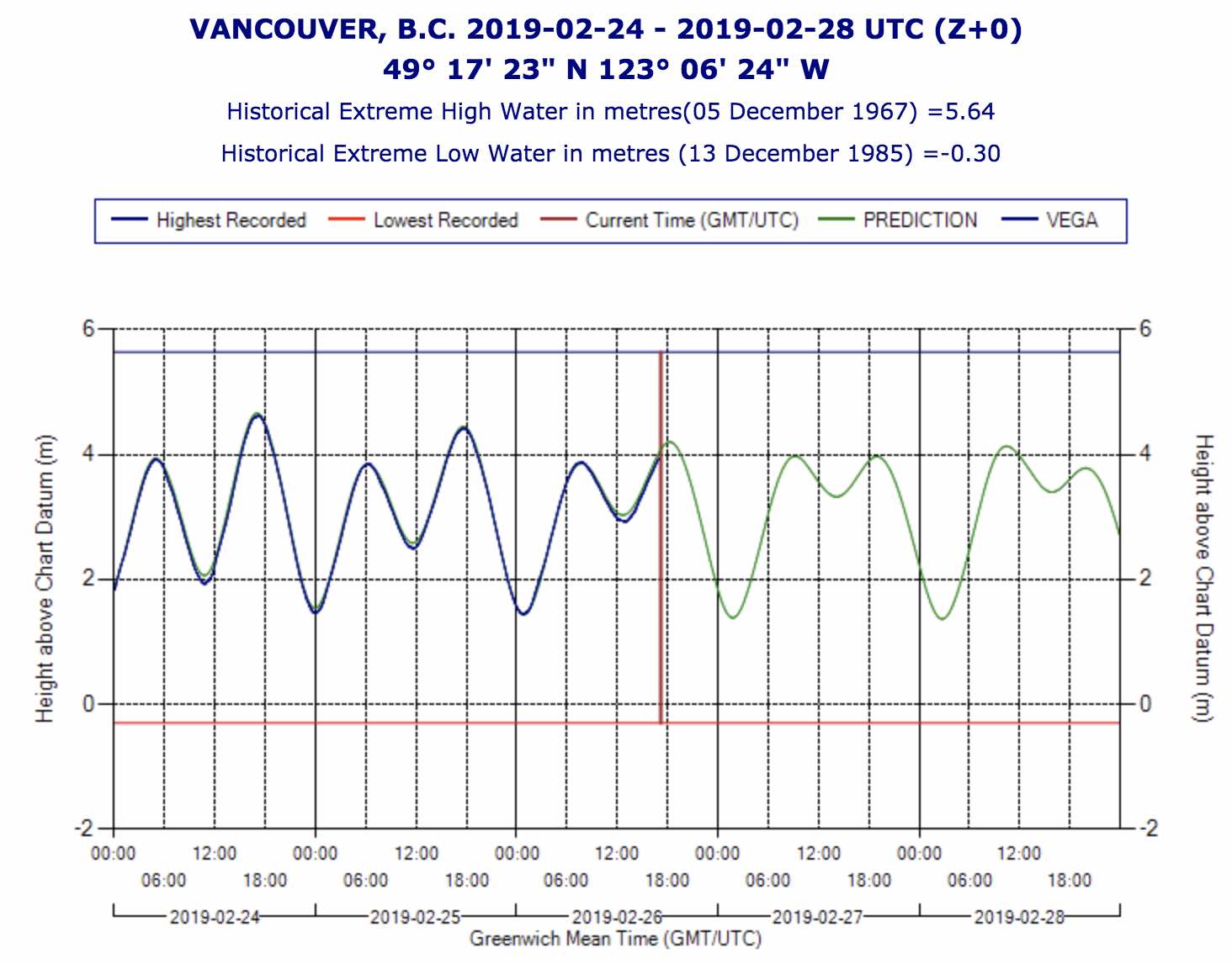

The tide is the movement of the

ocean surface up and down due to the gravitational pull of the moon

and sun. The following figure shows 5 days of the sea level rising and falling with the tides at Vancouver, BC.

Example of neap tides at Vancouver. Blue

line is observed, and green line is forecast. Source: Tide tables from

http://www.tides.gc.ca/eng/data#s4 .

The gravitational pull varies depending on the positions of the moon and sun, causing the tides to vary through time and space. The moon is closer to us, making its pull on the ocean greater than the sun’s. The gravitational forces of the sun and moon pull up the ocean’s surface at the point where they are closest to the Earth, creating a bulge, or a high tide. These bulges can also be thought of as waves of moving water that follow the sun and moon. As water rushes to form this bulge at some parts of the globe, the water level decreases somewhere else, creating a low tide. Thus high and low tides are occurring simultaneously across the oceans of the globe.

As the moon orbits around the earth each 29.5 days, its different

amounts of illumination as viewed from earth are called phases of the

moon. Recall that new moon is the name when the moon and sun are aligned, so the moon looks dark. Also, the name full moon is when the moon is on the opposite side of the earth from the sun, so the moon looks bright. Quarter moon

is the name when the sun and moon are at right angles to each other,

causing half of the moon to be illuminated as viewed from Earth.

- Phases of the moon. Plays as a video loop if opened in a web browser: https://simple.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phases_of_the_Moon#/media/File%3ALunar_libration_with_phase2.gif

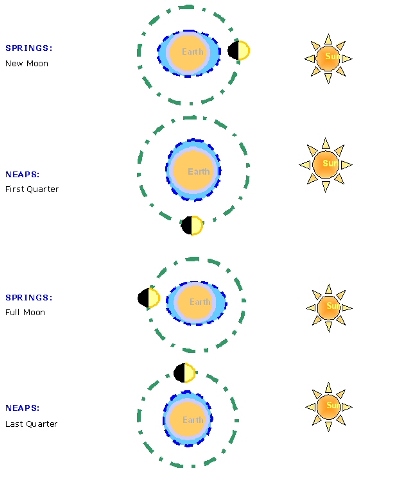

When the sun and moon line up (i.e. during full moon and new

moon), their forces add to each other, creating higher high tides and lower low

tides than usual. These are known as spring tides (Do not be fooled by the

name! Several days of Spring tides occur roughly twice every month). When the sun and moon are at

right angles to each other (i.e., quarter moons), they exert opposing forces on the oceans

and diminish each other’s strength, creating weaker or neap tides.

- Animation of tides, produced by NASA: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l37ofe9haMU

Source: User: Club Yachting - Own work, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9364268

The graph at the top of this page is centered on 26 Feb 2019, which

was when there was a "quarter moon". Namely, the sun and moon were at

right angles to each other, so the resulting neap tides had a small tidal range.

Namey, the high tides were not very high and the low tides were not

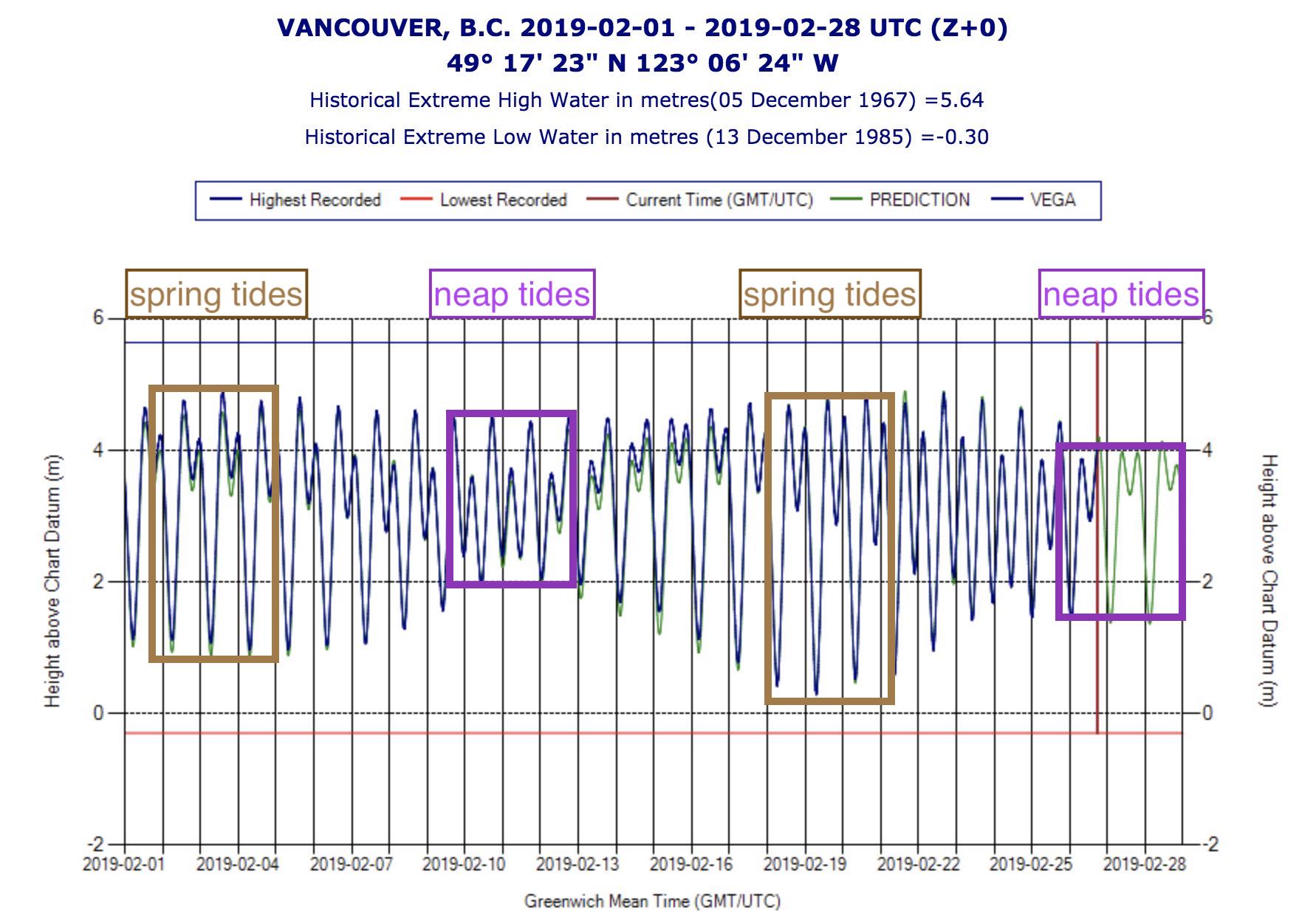

very low. Compare this with the next figure, also for Vancouver,

but

showing tides for the whole month of February 2019. As you can

see,

there were two spans of "spring tides" with large tidal range, and two

spans of "neap tides" with reduced tidal range. The "spring

tides" tidal range was approximately double the range of the "neap

tides".

A month of tides at Vancouver. The vertical size of the brown box outlines the tidal range of spring tides, and the purple box outlines the tidal range of neap tides. The last 5 days in this graph correspond to the figure at the top of this web page. Source: Tide tables from http://www.tides.gc.ca/eng/data#s4 .

The position of the moon and sun relative to the earth can be calculated well into the future, allowing us to also predict the strength and timing of the tides into the future. In fact, most countries publish annual tide tables at the beginning of the year. All sailors should be familiar with the tide tables for the waters they will be sailing in. There are lots of online resources for getting tidal information, as well as printed versions. We will go over how to read the tide tables in Section 11e.

You will typically see two full tide cycles per day, meaning two high tides and two low tides. It is important to time your journey with the tide to avoid any limitations to passage. The difference between the highest and lowest tide experienced in an area is called its tidal range and can give you a good indication of what the tides are like in one area relative to the next.

In case you are wondering, the first high tide, or bulge, is observed on the point on the Earth that is closest to the moon due to the moon’s gravitational force. The point on the opposite side of the Earth is then experiencing the least amount of pull from the moon than anywhere else, and so it is able to bulge in the opposite direction, away from the moon.

Tidal Current

The rising or falling of the tides creates currents, known as flood currents for the incoming tide and ebb currents for the outgoing tide. The currents are the horizontal movement of water, while the tide itself is the vertical movement of water. When sailing, knowing the timing and strength of the current tells you about how fast you can travel to your destination and perhaps what route you should take to get there.

Say you were planning a day sail from Coal Harbour in Vancouver, out under Lions Gate Bridge, over to Point Atkinson and back. If the tide is coming in when you set out, you will be fighting a fierce opposing tidal current under the bride and all the way out to Point Atkinson. This could reduce your over-the-bottom speed to 3 knots. Given that it’s 7 nautical miles from Coal Harbour to Point Atkinson, it would take you about 2.5 hours to get there! But if the tide were going out, the water would be travelling from Vancouver Harbour out under the bridge and out to the Strait of Georgia carrying you with it. You could be travelling at 6 knots over the bottom, and would get there in just over an hour! See the difference?

The moment when the tide turns and changes direction, the current

ceases and also changes direction. This moment of no current is called slack tide or slack current. You can have a high slack when the tide reaches its maximum height or a low slack

when the tide reaches its lowest height. Therefore, you can expect to

see two high slacks and two low slacks in a 24-hour period in most

places. Peak currents are therefore at the midpoint between high and

low tide. During larger than normal tides, you will also see larger

currents.

Currents are usually greater in the mid-channel or deepest part of the channel and weaker over shallower water. If you find yourself travelling against the current, try to navigate through waters where the current isn’t as strong. How can you tell which way the current is going? One way is to look at a buoy and see where the wake forms behind it. Or look at boats at anchor—if they are not pointing into the wind, there is likely a strong current that’s controlling their position.

Here’s a video I took of a sailboat trying to drive against the current under Lion’s Gate Bridge. We also happened to time our trip so we were returning to Vancouver against the current, however we used the shallower water near the sides of the channel where the current is weaker to get under the bridge. This other boat wasn’t as clever:

Here is another video of a sailboat struggling in a very strong current in Deception Pass (in Washington state 100 km south southeast of Vancouver): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4B3sd0XRFBE

Another thing to consider is the interaction between wind and current. When the wind and current are travelling together, the seas are calmer than when they are opposing each other. The turn of the tide can cause a relatively flat but windy channel to build into rolling waves and whitecaps. Sailors can often get tricked into going out in calm waters that seemingly build big waves ‘out of nowhere’. The strength of the wind hasn’t changed, but the tidal current has changed direction and the frictional force between the wind and water causes waves to form.

Tidal Rapids

When fast-flowing tidal currents are forced to pass through narrow channels, they can create dangerous tidal rapids with standing waves, large back eddies and intimidating whirl pools. At first sight, a passage at peak flood with raging rapids might look impassable, when in fact, you just showed up at the wrong time. These passages can be navigable in a sailboat, but only at slack current. If you miscalculate the slack and arrive too late, the current may have already become too strong and you may have to wait for hours before the next window of opportunity to pass.

One of the world’s fastest set of tidal rapids is right here on our doorstep: the Sechelt Rapids in Skookumchuk Narrows (just north of Vancouver). Here, the narrow opening between the Strait of Georgia and Sechelt Inlet sees flows of up to 17.6 knots as tidal currents push huge volumes of water through the narrows.

Skookumchuk Narrows:

Source: Kantokano - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=26434599

Whirlpool:

Source: Hellbuny - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3917656

Review of Tides & Tidal Currents

Here is a recap of the concepts.

High slack (zero current) and high tide (high sea-level elevation) occur at the same time. (They often appear to happen at different times in the tide and current tables because tide and current stations are not located in the same place. Thus, the difference in time merely represents the time lag between one station and the other as the water moves between them.) High slack refers to when the tide has come all the way up and pauses for a moment, causing current to drop to almost nothing, before reversing direction and going out as the tide drops.

In terms of 'which one is more important, high slack or high tide', that depends on the situation. If you're navigating through an area with high current, you will want to know when high or low slack is so that you're not travelling against the current as you travel through that area. Alternatively, if you're looking to pass over a shoal or shallow water, you'll want to know when the tide is high and when it is low so you don't run the risk of hitting the bottom.

In other words: "High slack is a period of zero current which happens at high tide before it ebbs". Namely, high slack is the moment when the water/tide has risen all the way up, and the current comes to a brief stop as it switches from flooding (water coming in/tide going up) to ebbing (water going out/tide going down). The inverse is that at low slack, the tide has gone all the way down and the current comes to a brief stop as it switches from ebbing to flooding.

To learn how to read published tide and current tables, see Learning Goal 11e .

Additional Resources: (non-required material)

Canadian Tide and Current Tables: https://charts.gc.ca/publications/tables-eng.html

NOAA Ocean Service Education - Tides and Water Levels): https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/education/tutorial_tides/welcome.html

Wikipedia – Skookumchuk Narrows: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Skookumchuck_Narrows

Video: (non-required material)

How do Tides Work?: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5ohDG7RqQ9I

Keywords: tide, tide tables, tidal range, flood current, ebb current, high slack, low slack, tidal rapids

Image credits: are given near the images.