ATSC113 Weather for Sailing, Flying & Snow Sports

Aspect Effects

Learning goal 7h: Describe the effects of aspect on surface snow evolution

Sun angle vs. compass direction

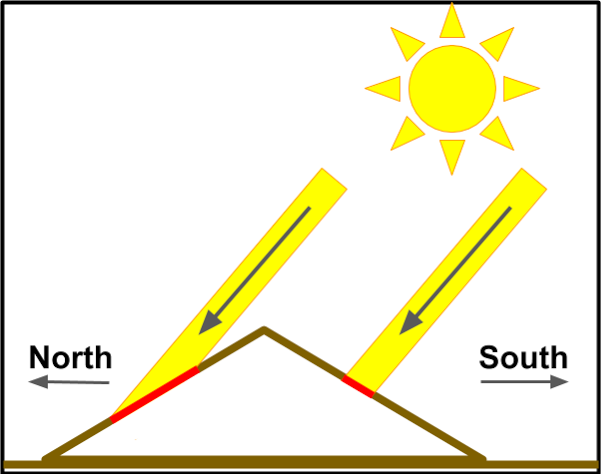

In this section we'll teach you how to use compass direction as a tool that finds powder, soft spring snow, and dangerous avalanche conditions. As we mentioned in Learning Goal 6i, the angle at which the sun strikes the earth's surface determines how concentrated its energy is over that part of the Earth's surface. A similar concept applies to mountain slopes. In the winter months, the sun is at a lower angle to the horizon. Also, it tends to be in the southern part of the sky, rising in the southeast and setting in the southwest. (By contrast, in Vancouver in June, the sun takes a longer arc across the sky, rising in the northeast and setting in the northwest). Therefore, in the winter, the sun strikes south-facing slopes more directly (Fig. 7h.1). Let's take a look:

Recall that "incoming solar radiation" (energy from the sun) can be referred to simply as insolation. In Fig. 7h.1, insolation strikes the south-facing slope at a more direct angle, and so the energy and heating is concentrated on a smaller area (a given amount of energy from the sun is concentrated over a relatively small portion of the slope).

By contrast, insolation strikes the north-facing slope at a less direct angle, and so the same amount of energy and heating is spread over a larger area. That is, a given amount of energy from the sun is spread out over a relatively large portion of the slope, so each part of the north-facing slope gets less heating energy. For the north-facing slope, if you take an area the same size as the red area on the south-facing slope, it will be receiving less radiation and will therefore not heat up as much.

In the extreme, such as a steep, north-facing slope (like a cirque), it may be in shadow most or all of the day in winter. This means it gets no direct insolation. (It does receive some indirect, diffuse insolation, so it does not appear like nighttime, but this is usually weak in comparison to direct insolation.)

Slopes that face east and west receive more insolation than north-facing slopes, but less than south-facing slopes. They also receive it at different times of the day. East- or southeast-facing slopes tend to get the sun first in the morning, when temperatures are usually coldest. South-facing slopes see their insolation peak at around midday, when temperatures are warmer. West- and southwest-facing slopes receive the most insolation in the afternoon, when temperatures are typically the warmest.

Aspect terminology

In the skiing and avalanche worlds "south-facing slopes" may be referred to as southerly aspects, or even sunny or solar aspects. Similar terminology is used for other aspects. For example, easterly aspects for east-facing slopes, westerly aspects for west-facing slopes, northerly or shady aspects for north-facing slopes. Further, a term like easterly aspects refers to not just east-facing slopes, but also northeast-facing and southeast-facing slopes — anything with an easterly component to it.

How does this help me find good snow?

When the sun's energy heats the snow surface to 0°C, it begins to melt. This means that wet and/or heavy snow is more often found on southerly and westerly aspects. This is because southerly aspects get the largest amount of insolation, and westerly aspects get insolation during the time of day when the air temperature is warmest. This is especially true in spring, when there is generally more solar radiation from the sun than in the winter (see below).

Even worse, if the snow surface refreezes overnight (which is more likely if there is no cloud cover), southerly and westerly aspects are where you're most likely to find crusts (see Learning Goal 7f). Conversely, northerly and easterly aspects are the most likely to be crust-free.

Since the sun's angle above the horizon increases as we get farther into spring, the amount of insolation also increases. That means that on a cold day in January, a south-facing slope can survive a sunny day without developing a crust. However, in late February or in March, southerly and westerly aspects are baked by noon, and will be crusty and unenjoyable the next morning.

In the spring, when temperatures are generally warmer, it is typical for the snow surface on all aspects to undergo a daily melt/freeze cycle. Skiers like to hit these slopes as the sun first softens them, but not to the point where the snow gets slushy and grabby. Using what we've learned here, we can surmise that easterly aspects will soften first, followed by southerly aspects. Westerly aspects often progress to slush too quickly to find good skiing on them (in springtime). Insolation on southerly and westerly slopes increases meltwater in the top layers of snow, increasing the chances for wet sluffs and wet slabs, which can be an issue in the backcountry.

The snow surface always emits IR radiation (heat energy proportional to its temperature). During the daytime, insolation counteracts and usually exceeds the amount of energy being emitted/lost (especially with little or no cloud cover). So the snow surface heats up. However, on north- (and sometimes east-) facing aspects, this situation can be reversed during the day, meaning the snow surface cools down.

On northerly aspects in winter, even when the air temperature (measured at 2-m above ground level) is above freezing, the snow surface can remain below freezing. Thus, northerly (and to a lesser extent easterly) aspects are the best aspects to find preserved powder during sunny periods. Your very best bet for finding preserved powder is on high-elevation slopes that are in the shade all or most of the day, so steep east- or north-facing slopes. The downside to those consistently colder snow surface temperatures is that those same spots are where faceting and surface hoar are most likely to be found (and the resulting persistent weak layers).

In summary, if you find you're encountering hard refrozen snow or crusts, then it is time to reconsider which aspect you are skiing on. Moreover, consider this before you head up the mountain! For the area you are skiing, ask yourself, "which aspect might have sun-softened snow, or preserved powder?"

Keywords: insolation, southerly aspects, solar

aspects, easterly aspects, westerly aspects, northerly aspects, shady

aspects, wet sluffs, wet slabs, faceting, surface hoar, persistent weak

layers

Figure Credits: Stull: Roland Stull, West: Greg West, Howard: Rosie Howard