ATSC 113 Weather for Sailing, Flying & Snow Sports

Resort Snow-Surface Conditions

Learning goal 7o: List possible snow-surface conditions found

in ski resorts and describe a possible weather scenario that leads to

each condition

Learning goal 7p: Give reasons why snow-surface conditions are

important to ski racers and recreational skiers

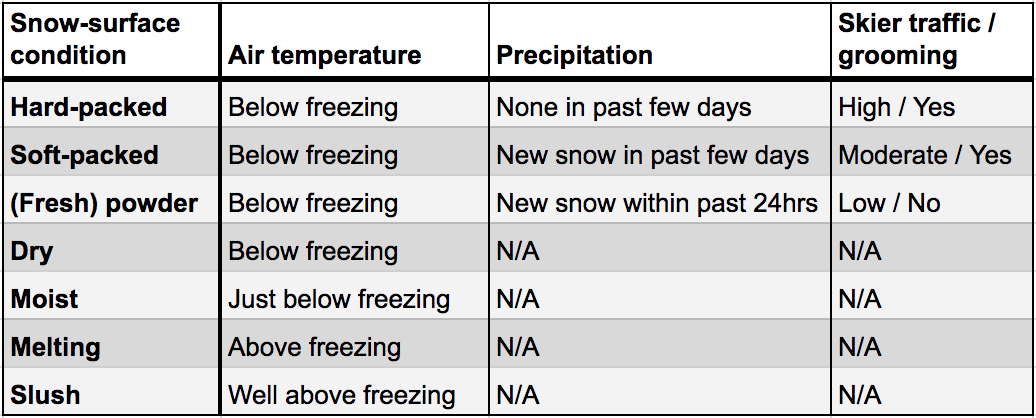

Snow and weather conditions are usually reported daily by ski resorts, appearing on notice boards on the mountain and on their website. Here our focus is on the range of snow-surface conditions that occur at a resort throughout a winter season. Table 7op.1 lists these (as well as a couple of others that may not be reported but you might hear about or experience) along with possible weather and resort conditions that could result in the snow surface being this way.

Table 7op.1 Summary of snow-surface conditions reported or found within ski resorts, and possible weather conditions that could lead to these conditions. Details and exceptions are provided in the text. "Skiers" refers to skiers or snowboarders. (Credit: Howard)

You will see conditions 1, 2, 3, and 7 reported fairly regularly by the average ski resort. Conditions 4 and 5 are not usually reported by ski resorts, but more specifically relate to the type of snow on the ground, which is related to the weather and also sometimes the location. Dry vs. moist snow can mean a great time vs. a more frustrating time. You will probably not hear condition 6 being reported with that terminology since melting snow is bad for business! Nonetheless, the above table will help you identify when might be the best time to go skiing, depending on the type of conditions you prefer. Note that there are always exceptions, but the descriptions of these conditions are based upon my average experience.

Another reason that snow conditions are important is that ski and snowboard racers apply wax to the base of their equipment in order to reduce friction and therefore increase the speed at which they travel. Some recreational skiers do this too but it's not as common since it doesn't matter as much to them how fast they travel. Different waxes are used for different air and snow temperatures and humidities, so understanding snow conditions is a first step into understanding the application of wax to your equipment.

Details and exceptions

-

Hard-packed

The snow surface becomes hard-packed when it hasn't snowed for a few days, and the snow surface has since been compressed by skiers or a grooming machine, or both. Here are two special cases:

- The snow report says corduroy - which sounds funny if you've never heard it before. The pictures in the link demonstrate the ridged effect that is left by the grooming snowcat. While this surface is considered hard, it is usually fun to ski on. It is uniform and you can reach fast speeds without worrying about catching an edge of your skis or snowboard, or sliding out because it's too icy. The snow-surface can become much harder via natural processes alone.

- The second special case has brought some of the hardest and most "icy" snow surfaces I have ever experienced (at Whistler Mountain). During an Arctic air outbreak (Learning Goal 6l), air temperatures are especially cold, and snow temperatures become so cold that any liquid water in the snowpack becomes frozen. An Arctic outbreak can persist for days or even weeks, where there is no new precipitation to make the snow surface softer again. This scenario is less fun to ski in, unless you like to go really fast, have very sharp edges on your skis or snowboard (to save you from sliding out onto the concrete-hard snow!), and are wearing warm clothing. Having skis is usually an advantage over having a snowboard in these conditions, since you have two edges to create friction while turning, instead of just one.

Recreational skiers might just choose to go slower if they know the piste is very hard-packed. Racers don’t want to have to slow down, so they use skis with very sharp edges.

-

Soft-packed

A soft-packed snow surface occurs when freshly fallen snow has been somewhat compressed by snowcats and skiers, and it is nice to ski on. It usually happens when it hasn't snowed for a day or two, or it has been or is lightly snowing (Fig. 7op.1) and there are skiers on the piste. In the photo, the piste has been groomed and then it snowed lightly, leaving just a couple of centimetres of soft powdery snow on top of the compressed piste. To the far right, there is an adjoining ski run that has had more traffic so is a bit more compacted but still soft.

Fig. 7op.1 - A ski piste with a soft-packed snow surface. Photograph taken on the Dave Murray downhill on Whistler Mountain, BC. (Credit: Howard)

-

Powder

Powder days are usually highly sought after as a skier or snowboarder. These follow a substantial snowfall of anywhere between about 10 cm and 50 cm - sometimes more! This is called fresh powder since it has just fallen and is untouched. Another way that "powder" occurs is by wind-loading. Loose snow is blown into gullies and just over ridgetops. Sometimes, when skiing off-piste, you can find these powder stashes even if it hasn't snowed for a few days, because the wind has piled it up for you. Different densities of powder were covered in detail in Learning Goals 7b and 7c. -

Dry

In general we say that snow on the ground is dry if there is no liquid water in the snowpack, although in reality most snowpacks contain a very small amount of liquid water. Sometimes conditions can cause snow that fell as wet or moist snow to dry out, but this is quite rare especially near the coast, and where lots of traffic is passing over the snow surface as occurs in a ski resort.

The amount of moisture in the snowpack is determined by very complex processes that occur while it is falling and once it is on the ground. To keep things simple here, we will say that dry snow occurs for two reasons:

- Location. The BC Interior is famous for its champagne powder snow (though the term originated in the US Rocky Mountains), which is very dry and fine snow - a dream to ski in. See Learning Goal 7g for more details on regional characteristics of snowpacks.

- Very low temperatures, e.g. due to a particularly cold frontal passage.

-

Moist

As mentioned above, snowpack moisture is influenced by several complex processes. Again, keeping things simple, moist snow-surface conditions occur due to:

- Location. Generally speaking, snow in the coast mountains contains more moisture than in the BC Interior. Again, see Learning Goal 7g for more details.

- Warm temperatures, e.g. due to a warm frontal passage. In an extreme case, you might hear people refer to the snow as being like cement. This means the snow is very high in liquid water content. Even though lots of snow may have fallen, it is very dense and easy to get stuck in if you are not travelling fast enough or the slope is not steep enough.

-

Melting

When I think about melting snow, I recall snowboarding down a fairly gentle slope in springtime, when the afternoon sun is shining but some trees are casting a shadow over parts of the slope. As I snowboarded over the parts of the piste that were in the sun, my snowboard began to slow down and felt like it was suctioned to the snow. When I travelled into a shaded area, my snowboard began to speed up again. The snow in the sun had warmed up to 0°C and started to melt, meaning there was more liquid water in the snowpack and at the snow surface. This increases friction, and is exactly why you would use a different wax for warmer/more humid conditions. As a recreational snowboarder it's a minor annoyance to me, but if I was racing I would want to optimize the type of wax to the conditions on the ski slope. Probably the most common temperature-dependent waxing that recreational skiers do is putting on warm-temperature "spring wax" in the springtime, to try and reduce this "suction" feeling you get on warm spring days.

-

Slush

You will usually find slush conditions during the springtime in the afternoon. Basically, the whole top layer of snow is melting. By late spring, the entire depth of the snowpack can reach a temperature of ~0°C during the afternoon, and we say it is isothermal. Slush can be quite fun to ski in, since the snow is soft and moves around like powder would. However, it is a lot heavier and more dense due to the high liquid water content.

Keywords: cold frontal passage, fresh powder, hard-packed, location, slush, soft-packed, warm frontal passage

Figure Credits

Howard: Rosie Howard

West: Greg West

Stull: Roland Stull

COMET/UCAR: The source of this material is

the

COMET® Website at http://meted.ucar.edu/ of the University Corporation

for Atmospheric Research (UCAR), sponsored in part through cooperative

agreement(s) with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

(NOAA), U.S. Department of Commerce (DOC). ©1997-2016 University

Corporation for Atmospheric Research. All Rights Reserved.

NOAA: www.nws.noaa.gov

Google: Map data (c) 2016 Google