"Disease detectives" solve decade-long mystery of sea star wasting disease

An international research team identified the cause of the devastating sea star wasting disease (SSWD) that has wiped out 90% of sunflower sea stars (Pycnopodia helianthoides) over the past decade. The culprit: Vibrio pectenicida strain FHCF-3.

The discovery was recently featured on the cover of Nature Ecology and Evolution (NEE), with the draft genome of V. pectenicida FHCF-3 reported in Microbiology Resource Announcements (MRA).

This breakthrough was made possible through a multi-institutional collaboration involving researchers from the University of British Columbia (UBC), the Hakai Institute, the University of Washington, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, the U.S. Geological Survey, the University of Vermont, and Cornell University.

“It’s really a team effort that pulled this together,” said Curtis A. Suttle, one of the leaders of the project, and Professor and Principal Investigator of Aquatic Microbiology & Virology Lab at the Department of Earth Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences (EOAS) at UBC. Key contributors from the Suttle Lab included: Melanie B. Prentice (Research Associate), Amy M. Chan (Research Scientist), Kevin X. Zhong (Research Associate), Jan F. Finke (Research Associate), Katherine M. Davis (Postdoctoral Researcher), and Yasmine Gouin (Undergraduate Research Assistant).

A Decade of Destruction

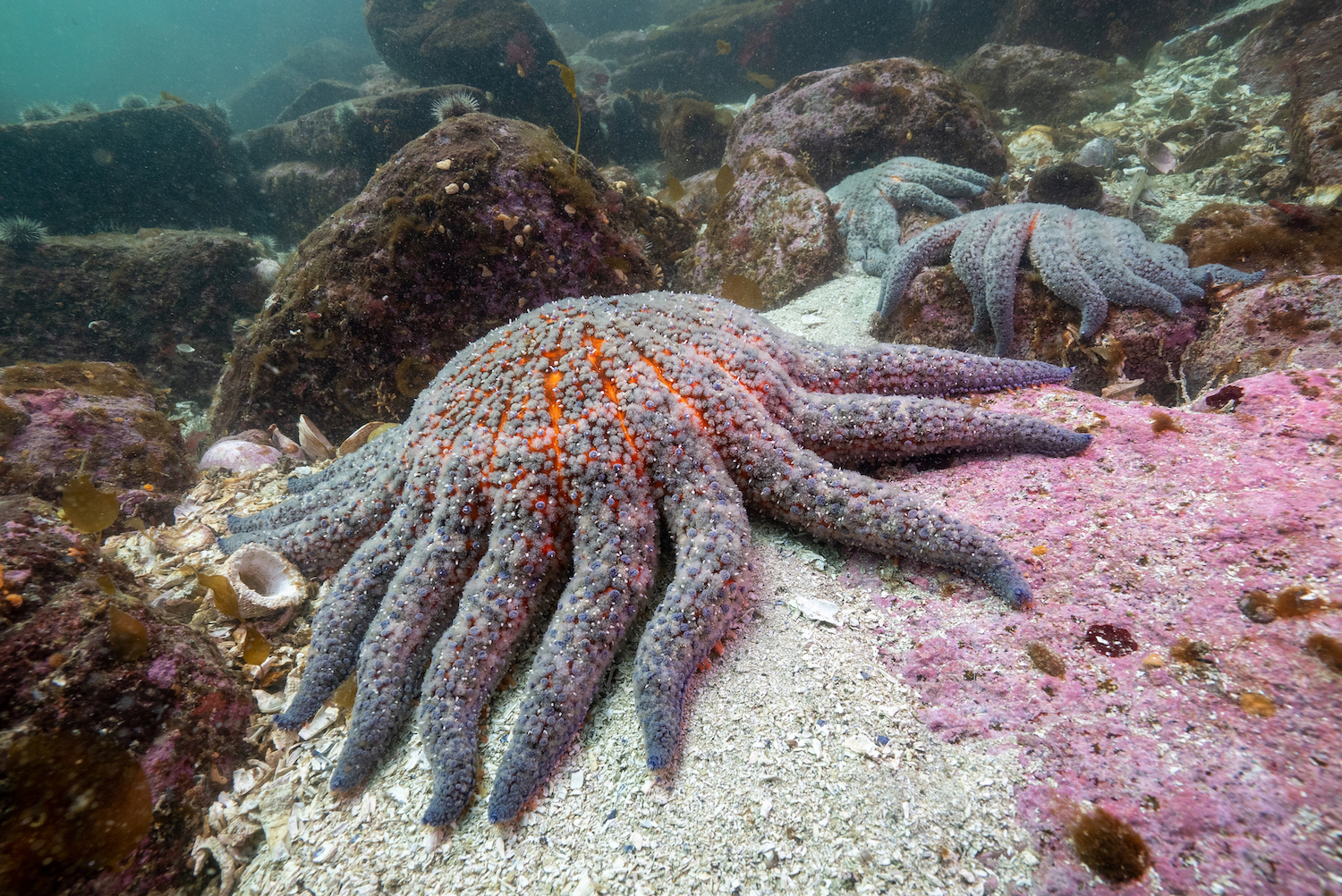

Since 2013, SSWD has caused the deaths of billions of sea stars from Mexico to Alaska. It begins with lesions and progresses rapidly, “melting” sea star tissues in about two weeks. “Losing a sea star goes far beyond the loss of that single species,” said Melanie B. Prentice, first author of the NEE study, Research Associate at EOAS and Hakai. “In the absence of sunflower stars, sea urchin populations increase, which means the loss of kelp forests, and that has broad implications for all the other marine species and humans that rely on them.”

Wasting sunflower sea star off Calvert Island, British Columbia, in 2015. Credit: Grant Callegari, Hakai Institute

Urchin barren in Hakai Pass in 2019. The decline of sunflower sea stars has led to proliferation of urchins and a widespread loss of kelp. Credit: Grant Callegari, Hakai Institute

Melanie B. Prentice (right) and Grace A. Crandall in the U.S. Geological Survey’s Marrowstone Marine Field Station. Credit: Bennett Whitnell, Hakai Institute

Finding the Culprit

The team compared healthy sea stars with those exposed to SSWD through contaminated water, infected tissue or coelomic fluid—sea star “blood.” “When we looked at the coelomic fluid of exposed and healthy sea stars, there was just one thing different: Vibrio,” said Alyssa M. Gehman, senior author of the NEE study, an Adjunct Professor at UBC’s Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries and a marine disease ecologist at the Hakai Institute. “We all had chills. We thought, ‘That’s it. We have it. That’s what causes wasting.’”

Alyssa M. Gehman checking on an adult sunflower sea star in the Marrowstone Marine Field Station. Credit: Kristina Blanch, Hakai Institute

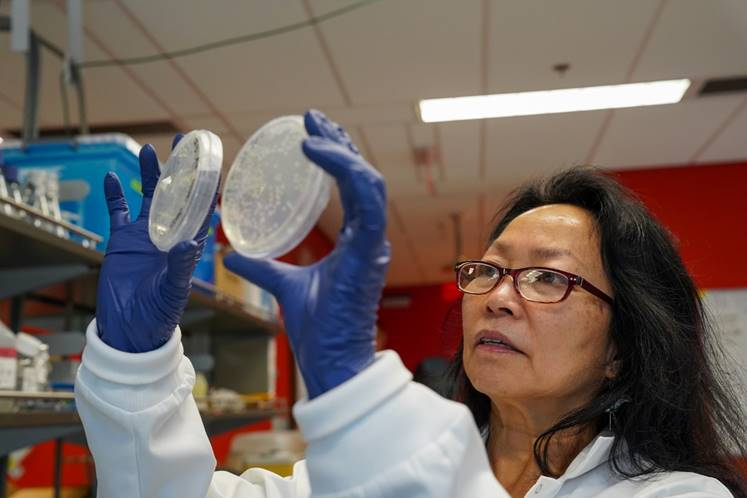

From there, EOAS Research Scientist Amy M. Chan established pure cultures of V. pectenicida FHCF-3 from the coelomic fluid of sick sea stars. When injected into healthy sea stars, all developed symptoms and died within days, conclusively proving the role of the bacterium in SSWD. “Using DNA sequencing, we saw there was a huge signal of a particular bacterium. This was our prime suspect to isolate. When I did, I saw basically only one kind of bacteria growing on the plates and thought, ‘This has got to be it,’” said Amy.

The isolation of V. pectenicida FHCF-3 is “a really, really big finding”, added Curtis in an interview with CBC. “Many people have been looking at this for more than a decade, and have been unable to figure out what is it that’s decimating the sea star population.”

Amy M. Chan comparing bacteria cultures from a sick versus a healthy sea star. The culture from the sick sea star (right) contains V. pectenicida. Credit: Toby Hall, Hakai Institute

Delving into the Genome

Building on the isolation of V. pectenicida FHCF-3, Kevin X. Zhong, first author of the MRA study and EOAS Research Associate, led the genome analysis of the bacterium. V. pectenicida FHCF-3 was found to have the genetic potential to produce aerolysin-like toxins, which may disrupt cellular membranes and drive the disease process.

“The complete genome of V. pectenicida strain FHCF-3 is a valuable resource,” said Kevin. “It provides a detailed map of the bacterium’s genetic blueprint, offering clues about how it might cause disease and guiding future research to detect, prevent, and control SSWD.”

Kevin X. Zhong in the Aquatic Microbiology & Virology Lab (Suttle Lab) at UBC. Credit: Zhe Cai

Looking Forward

The researchers hope the discovery will pave the way for recovery strategies for sea stars and the ecosystems they support. “Now that we’ve identified the disease-causing agent, we can start looking at how to mitigate the impacts of this epidemic,” said Melanie.

Watch our interview with Dr. Prentice!

Watch more interviews with the research team via the Hakai Institute, The Canadian Press, Global News, CBC News (here and here)

Read more coverage in: UBC News, Science, Nature Research Highlights, The Tula Foundation, USGS, CBC News, National Post, Global News, The Globe and Mail, The Conversation, Vancouver Sun, Glacier Media (via North Shore News, Richmond News, Vancouver is Awesome, Pique NewsMagazine, Times Colonist, Squamish Chief, Business in Vancouver (BIV), Bowen Island Undercurrent, Powell River Peak, and Sechelt / Gibsons Coast Reporter), The New York Times, The Washington Post, Discover Magazine, Los Angeles Times, USNews, NBC, CBS, ABC, 中国科学报, CNN Brazil, The Guardian, The Independent, Sky News, Natural History Museum.

Follow news releases on this discovery here: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41559-025-02797-2/metrics