News

Stay up-to-date with what's happening in EOAS

Professor Catherine Johnson Awarded Killam Research Prize

The Department is pleased to announce that Professor Catherine Johnson has been awarded the Killam Research Prize, an award which recognizes the outstanding research contributions of faculty from across all disciplines. Prize recipients are celebrated for creating and disseminating knowledge that has a global impact.

Dr. Johnson’s work is more than global, and focuses on the history and evolution of terrestrial planets – namely, Mercury, Mars and Venus. She uses remotely-sensed geophysical data to better understand the history and evolution of terrestrial planets, and has worked on several NASA planetary missions, including the Mars InSight mission and the Mercury MESSENGER mission. Her current work aims to understand the magnetic fields of Mercury and Mars, including when and why they formed, their current state, and how the fields interact with the solar wind. “A huge unknown” she explains, “is the level to which magnetic fields protect a planet’s atmosphere from space weather”, a question with implications for human space exploration and habitability in this solar system and beyond.

Her work also focuses on planetary evolution and internal structure, and what that means for current planetary seismic and volcanic activity. Dr. Johnson works with a wide range of remotely sensed data, including altimetry, radar and gravity measurements. Data is collected by lightweight, low-power, instruments specifically designed to resist the challenges of operating in space.

“You’re required to be very creative, in a responsible way” she says of the intrinsic limitations on data quality and availability. Leaps and bounds in instrument technology between missions means that new data can improve on in resolution by an order of magnitude or more, revealing in detail features that may have previously taken up only a handful of pixels. “I love it; with each new mission to a planet or moon or asteroid you almost always see something unexpected.”

Looking forward, Professor Johnson is excited for multiple upcoming missions to Venus which will collect data on the composition and structure of the planet’s atmosphere and surface. She plans to answer questions about Venus’ suspected volcanic and tectonic activity using data previously shrouded from view by the planet’s thick, toxic atmosphere. “Venus was my first planet” she says, referring to the geophysical work she did on the planet during her PhD and postdoctoral studies. “It is so different from the Earth in so many ways, but would look equally habitable to our planet from a galaxy away – why is that?”

Though not directly involved in the upcoming missions, Dr. Johnson will have access to the resulting publicly available data. With datasets so sparse and expensive to obtain, collaboration is a driving force in propelling the field of planetary science forward. She stresses the key role it has played in her research group’s success: “this award is an honour, and it’s not about me; its about the people who I’ve had the privilege to work and collaborate with.”

Professor Johnson (2nd from right) and recent research group members Megan Russell, Anna Mittelholz, Anna Grau, and Georgia Peterson at the Lunar and Planetary Sciences Conference

Dr. Shandin Pete talked about Indigenous scientific knowledge of hydrology and astronomy

Dr. Shandin Pete, Assistant Professor of Teaching in the Department of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences at the University of British Columbia, is investigating connections between natural phenomena and Indigenous scientific knowledge.

Check out the recent episode of the CBC radio show The Early Edition where Dr. Pete talked about Indigenous hydrology and astronomy.

To learn more about what scientific clues Dr. Pete found Indigenous stories reveal, check out the article by UBC News: Indigenous stories reveal the science of the world around us.

Dr. Pete is a hydrogeologist and science educator with interest in Indigenous research methodologies, geoscientific ethnography, Indigenous astronomy, social-political tribal structures, culturally congruent instructional strategies, and indigenous science philosophies. Most of his work in recent years has focused on community engagement to understanding shifts in an Indigenous paradigm of research for science knowledge production. This work has included extensive collaboration with tribal knowledge holders across Native communities and Indigenous academic scholars at institutions nationally and internationally.

Professor Curtis Suttle interviewed in the CBC radio show North by Northwest

Dr. Curtis Suttle (FRSC, Distinguished University Scholar) is a professor in the Department of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences at the University of British Columbia. Dr. Suttle was recently interviewed in the CBC radio show North by Northwest and discussed his research on how viruses are essential to our existence.

Research in the Suttle laboratory is primarily focused on viruses and their role in the environment. The work ranges from the characterization of viruses isolated from the environment to quantifying the role of viruses in microbial mortality and nutrient cycling. The techniques employed range from nucleic-acid sequencing to oceanographic sampling. Some current projects are examining viruses and their roles in the oceans, high Arctic, deep mines, aeolian dust, lakes and migratory-bird ponds.

Check out the podcast here: https://muckrack.com/podcast/north-by-northwest-from-cbc-radio-british-…

Simulating polarimetric radar data from weather forecasts - Anthony Di Stefano

Imagine that a weather forecast model could see the weather in the atmosphere like radar! Anthony Di Stefano, PhD student in Atmospheric Sciences at EOAS, introduces his AGU21 presentation on evaluation of weather research and forecasting microphysics schemes using polarimetric radar data.

Meet Dr. Garry Clark - Glaciologist

Garry Clarke received his doctorate in physics in 1967 from the University of Toronto and is currently Emeritus Professor of Geophysics in the Department of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences at the University of British Columbia. His research speciality is glaciology and his particular expertise is in subglacial physical processes, subglacial hydrology, the stability of glaciers and ice sheets, and cryospheric agents of abrupt climate change. He spearheaded a 35-year glaciological field study in Yukon, Canada, that involved drilling and extensive use of subglacial instrumentation and he remains active in the development of theory and computational models of glacier and ice sheet dynamics. Clarke has served as President of the International Glaciological Society and the Canadian Geophysical Union and received the highest scientific awards of both these organizations. He was a lead author of the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and a contributing author to the Fourth Assessment. Clarke is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada, the American Geophysical Union, and the Arctic Institute of North America.

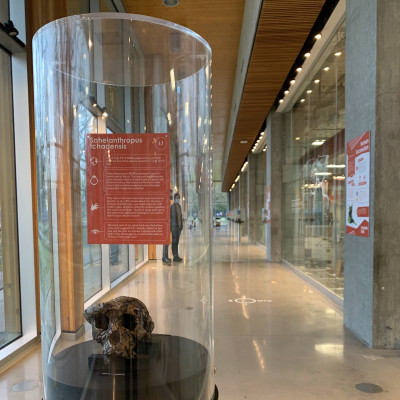

New Exhibit: Hominin Hallway

The Pacific Museum of Earth (PME) is hosting a family reunion millions of years in the making in their new exhibit: the Hominin Hall. The PME’s Hominin Hall explores the story of human evolution, starting our narrative 7 million years ago in Chad with Sahelanthropus tchadensis and concluding with our own species –Homo sapiens– and our uncertain future on our fragile planet. In this exhibit, visitors will delve into the lives of ten different hominins and explore how some characteristics and ways of life, from bipedalism to omnivory, came to define our lineage and continue in our own lives.

The replica skulls used in this exhibit were purchased in 2019 with a UBC Academic Equipment Fund for use in several EOAS courses and for display in the PME with the goal of showing the relative blink of an eye that humans have played in the long stretch of deep geologic time, by placing human evolution in a temporal context in the overall arc of the evolution of the biosphere. As visitors walk through this gallery, they will be confronted with the daily flow of UBC students walking up and down Main Mall, whose motion amplifies the dynamic story of human history we aim to tell and illustrates our condition as the last hominins of what was once a much larger family tree. In addition, the Hominin Hall’s placement in the front hallway of the Earth Sciences Building will provide a “zoomed-in” version of the last 7 million years of the Walk Through Time, an upcoming exhibit soon to be visible just outside the gallery windows.