News

Stay up-to-date with what's happening in EOAS

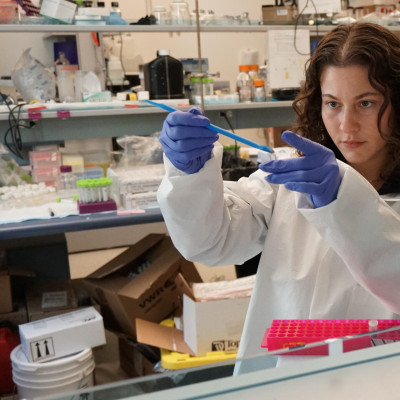

Asteroid Bennu holds clues to the origin of our solar system

In August, results from the first geochemical analyses of samples collected from asteroid Bennu by NASA’s OSIRIS-REx spacecraft were published in three journals, including Nature Astronomy. Dr. Dominique Weis, Director of the Pacific Centre for Isotopic and Geochemical Research (PCIGR) and Killam Professor in the Department of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences (EOAS) at the University of British Columbia, Dr. Marghaleray Amini, Research Associate and a Senior Lab Manager at PCIGR, and Vivian Lai (MSc), a Research Assistant at PCIGR, were among the international team of scientists who co-authored the study.

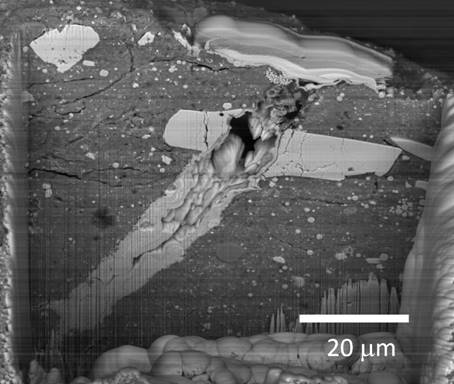

A scanning electron microscope image of a micrometeorite impact crater in a particle of material collected from asteroid Bennu. Credit: NASA Johnson Space Center

By studying Bennu’s elemental and isotopic makeup, the scientists traced its history back to a larger parent asteroid that broke apart after a collision, likely in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. That parent body formed over 4.5 billion years ago, during the birth of our solar system, from material with diverse origins—near the Sun, in the colder outer solar system, and even from other stars. “The variety of material that makes up Bennu is much greater than we could have imagined at the beginning,” said Dr. Weis. “There are even some pieces of Bennu that might predate the creation of our solar system. We have just a few grains, a few grams, that tell a very long history.”

Comparisons between Bennu, Ryugu (a similar asteroid sampled by the Japanese Hayabusa 2 mission), and Ivuna-type (CI) carbonaceous chondrite meteorites found on Earth suggest that their parent asteroids may have originated in the same region of the early solar system. However, Bennu stands out due to its higher levels of organic matter, anhydrous silicate minerals, and lighter isotopes of potassium and zinc. These differences suggest that the building blocks in that region either shifted over time or were not as evenly mixed as once thought. Remarkably, some of Bennu’s components appear to have survived heat, water, and even the violent collision that created the asteroid itself. “It's interesting on many levels because it reflects the original or older composition of the solar system, and it also allows us to understand how we arrived at the composition of the Earth that we have today,” said Dr. Weis.

Mass spectrometers at one of PCIGR’s analytical laboratories. Credit: D. Weis

PCIGR played a key role in these discoveries, analyzing the inorganic components of the Bennu samples for major and trace elements at extremely low concentrations. The team spent months optimizing sample handling methods and PCIGR’s highly sensitive, state-of-the-art mass spectrometers by analyzing reference meteorites of expected similar composition to Bennu. From the 121 grams of Bennu material that were returned to Earth in September 2023, Canada received 4% or almost 5 grams. PCIGR received enough material to carry out and repeat a series of analyses using the fine-tuned and thoroughly tested analytical protocols. The team carefully prepared and analyzed the elemental compositions of the Bennu samples, while ensuring they remained uncontaminated.

“These analyses will help us to understand the origin and evolution not only of the parent body of this asteroid, but also of our entire solar system and other planetary bodies in time and space,” stated Dr. Amini.

Another PCIGR-led publication on Bennu is in progress—stay tuned.

Read more:

- Listen to Dr. Weis’s interview on Radio Canada, in the show “Les années lumière”: Les analyses des échantillons de Bennu : Entrevue avec Dominique Weis

- Watch this video to learn about the research projects and facilities at PCIGR, including their work on Bennu: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p4J8F568ooc

- Check out Dr. Weis’s interview with UBC from the early stages of this exciting journey: Bits of Bennu asteroid to arrive at UBC

Dr. Laura Lukes wins Outstanding Paper Award from the Journal of Geoscience Education

Dr. Laura Lukes, Assistant Professor in the Department of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences, has been honored with the Outstanding Paper Award 2025 selected by the Journal of Geoscience Education, the leading international journal for research on how geoscience is taught and learned.

The award-winning article, co-authored by Dr. Lukes, is titled The geoscience education research (GER) community of practice: a brief history and implications from a needs assessment survey. With more than 1,000 views as of August 2025, it is already making a significant impact.

The article is a 10-year follow up to a landmark 2015 paper led by Dr. Lukes, Creating a community of practice around geoscience education research: NAGT-GER, which defined geoscience education research (GER) and its community of practice in discipline-based education research (DBER).

The new study examines how the GER community has grown over the past decade since the founding of the GER Division of the National Association of Geoscience Teachers (NAGT). Drawing on survey responses from 107 GER community members, the research identifies where the community is and what it needs to grow. Importantly, it fills in gaps from the foundational disciplinary DBER Report and helps establish the status and future directions of geoscience DBER in advance of the upcoming “Status of the Field of Discipline-Based Education Research” workshop, organized by the US National Academies of Sciences and scheduled in November 2025.

By receiving this award, Dr. Lukes and her co-authors have not only contributed to the ‘advancement of the discipline of geoscience education’ but also provided an important resource to represent geoscience education in the broader DBER conversation.

"Disease detectives" solve decade-long mystery of sea star wasting disease

An international research team identified the cause of the devastating sea star wasting disease (SSWD) that has wiped out 90% of sunflower sea stars (Pycnopodia helianthoides) over the past decade. The culprit: Vibrio pectenicida strain FHCF-3.

The discovery was recently featured on the cover of Nature Ecology and Evolution (NEE), with the draft genome of V. pectenicida FHCF-3 reported in Microbiology Resource Announcements (MRA).

This breakthrough was made possible through a multi-institutional collaboration involving researchers from the University of British Columbia (UBC), the Hakai Institute, the University of Washington, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, the U.S. Geological Survey, the University of Vermont, and Cornell University.

“It’s really a team effort that pulled this together,” said Curtis A. Suttle, one of the leaders of the project, and Professor and Principal Investigator of Aquatic Microbiology & Virology Lab at the Department of Earth Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences (EOAS) at UBC. Key contributors from the Suttle Lab included: Melanie B. Prentice (Research Associate), Amy M. Chan (Research Scientist), Kevin X. Zhong (Research Associate), Jan F. Finke (Research Associate), Katherine M. Davis (Postdoctoral Researcher), and Yasmine Gouin (Undergraduate Research Assistant).

A Decade of Destruction

Since 2013, SSWD has caused the deaths of billions of sea stars from Mexico to Alaska. It begins with lesions and progresses rapidly, “melting” sea star tissues in about two weeks. “Losing a sea star goes far beyond the loss of that single species,” said Melanie B. Prentice, first author of the NEE study, Research Associate at EOAS and Hakai. “In the absence of sunflower stars, sea urchin populations increase, which means the loss of kelp forests, and that has broad implications for all the other marine species and humans that rely on them.”

Wasting sunflower sea star off Calvert Island, British Columbia, in 2015. Credit: Grant Callegari, Hakai Institute

Urchin barren in Hakai Pass in 2019. The decline of sunflower sea stars has led to proliferation of urchins and a widespread loss of kelp. Credit: Grant Callegari, Hakai Institute

Melanie B. Prentice (right) and Grace A. Crandall in the U.S. Geological Survey’s Marrowstone Marine Field Station. Credit: Bennett Whitnell, Hakai Institute

Finding the Culprit

The team compared healthy sea stars with those exposed to SSWD through contaminated water, infected tissue or coelomic fluid—sea star “blood.” “When we looked at the coelomic fluid of exposed and healthy sea stars, there was just one thing different: Vibrio,” said Alyssa M. Gehman, senior author of the NEE study, an Adjunct Professor at UBC’s Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries and a marine disease ecologist at the Hakai Institute. “We all had chills. We thought, ‘That’s it. We have it. That’s what causes wasting.’”

Alyssa M. Gehman checking on an adult sunflower sea star in the Marrowstone Marine Field Station. Credit: Kristina Blanch, Hakai Institute

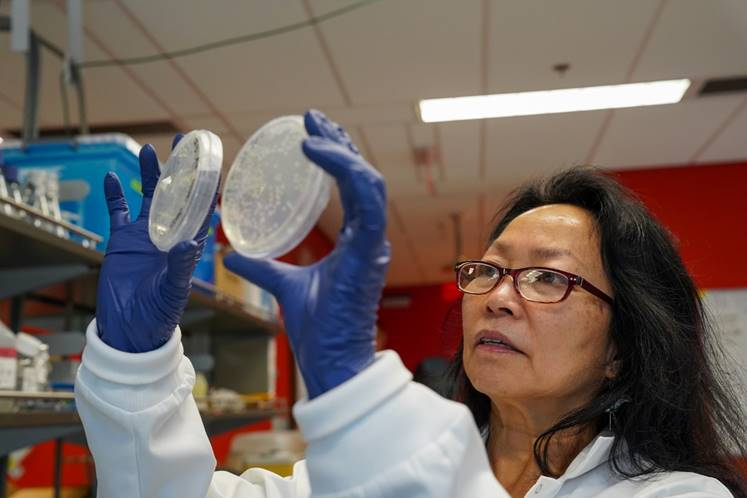

From there, EOAS Research Scientist Amy M. Chan established pure cultures of V. pectenicida FHCF-3 from the coelomic fluid of sick sea stars. When injected into healthy sea stars, all developed symptoms and died within days, conclusively proving the role of the bacterium in SSWD. “Using DNA sequencing, we saw there was a huge signal of a particular bacterium. This was our prime suspect to isolate. When I did, I saw basically only one kind of bacteria growing on the plates and thought, ‘This has got to be it,’” said Amy.

The isolation of V. pectenicida FHCF-3 is “a really, really big finding”, added Curtis in an interview with CBC. “Many people have been looking at this for more than a decade, and have been unable to figure out what is it that’s decimating the sea star population.”

Amy M. Chan comparing bacteria cultures from a sick versus a healthy sea star. The culture from the sick sea star (right) contains V. pectenicida. Credit: Toby Hall, Hakai Institute

Delving into the Genome

Building on the isolation of V. pectenicida FHCF-3, Kevin X. Zhong, first author of the MRA study and EOAS Research Associate, led the genome analysis of the bacterium. V. pectenicida FHCF-3 was found to have the genetic potential to produce aerolysin-like toxins, which may disrupt cellular membranes and drive the disease process.

“The complete genome of V. pectenicida strain FHCF-3 is a valuable resource,” said Kevin. “It provides a detailed map of the bacterium’s genetic blueprint, offering clues about how it might cause disease and guiding future research to detect, prevent, and control SSWD.”

Kevin X. Zhong in the Aquatic Microbiology & Virology Lab (Suttle Lab) at UBC. Credit: Zhe Cai

Looking Forward

The researchers hope the discovery will pave the way for recovery strategies for sea stars and the ecosystems they support. “Now that we’ve identified the disease-causing agent, we can start looking at how to mitigate the impacts of this epidemic,” said Melanie.

Watch our interview with Dr. Prentice!

Watch more interviews with the research team via the Hakai Institute, The Canadian Press, Global News, CBC News (here and here)

Read more coverage in: UBC News, Science, Nature Research Highlights, The Tula Foundation, USGS, CBC News, National Post, Global News, The Globe and Mail, The Conversation, Vancouver Sun, Glacier Media (via North Shore News, Richmond News, Vancouver is Awesome, Pique NewsMagazine, Times Colonist, Squamish Chief, Business in Vancouver (BIV), Bowen Island Undercurrent, Powell River Peak, and Sechelt / Gibsons Coast Reporter), The New York Times, The Washington Post, Discover Magazine, Los Angeles Times, USNews, NBC, CBS, ABC, 中国科学报, CNN Brazil, The Guardian, The Independent, Sky News, Natural History Museum.

Follow news releases on this discovery here: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41559-025-02797-2/metrics

New giant RNA virus discovered during mass oyster die-offs

Read the full article via UBC News: New mega RNA virus may hold the key to mass oyster die-offs.

Scientists have identified a previously undocumented virus, Pacific Oyster Nidovirus 1 (PONV1), associated with farmed Pacific oysters during a mass die-off in B.C., Canada. This finding, recently featured on the cover of Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, is remarkable because PONV1 has an extraordinarily large genome of 64 kilobases (kb) – making it one of the largest RNA virus genomes ever recorded.

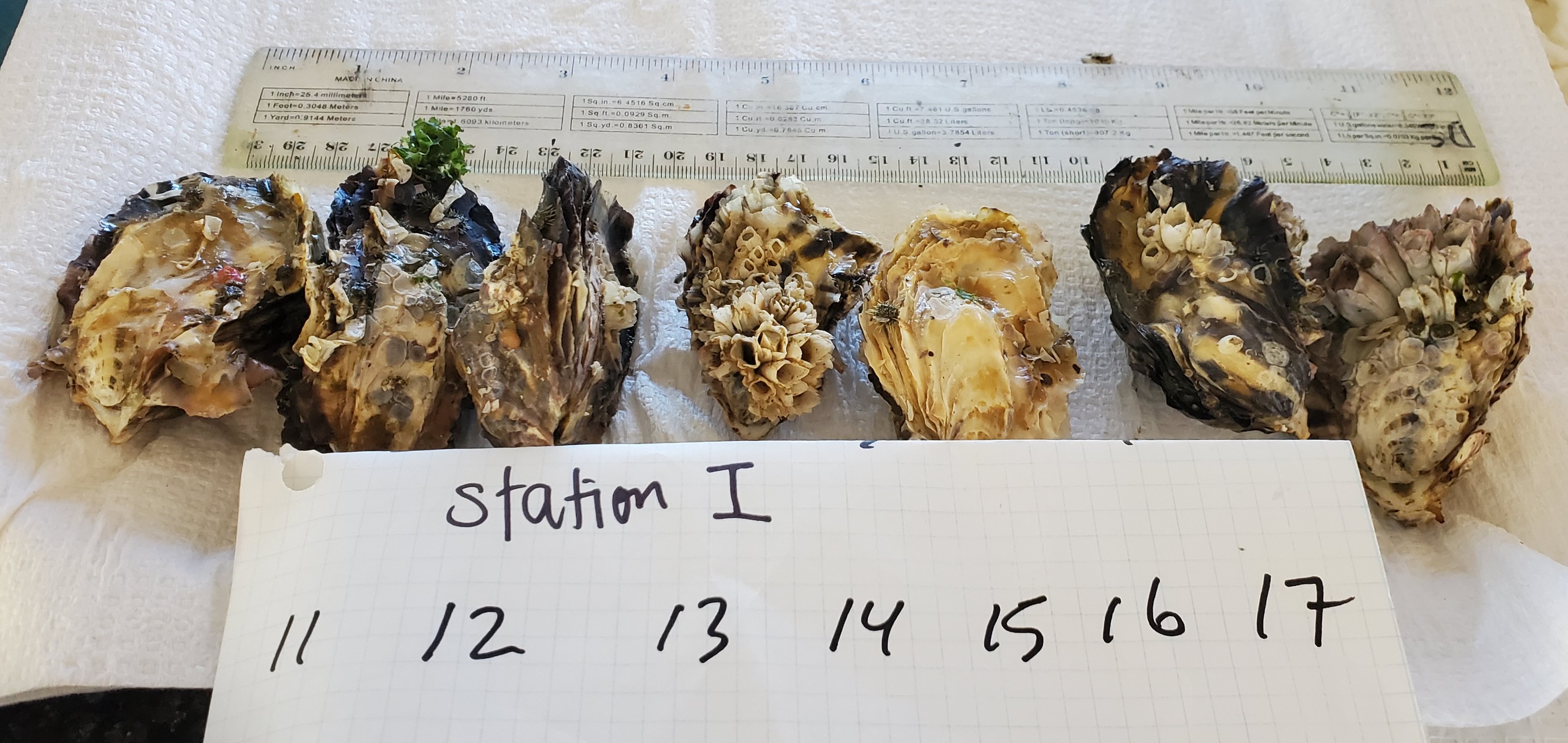

Pacific oysters are the most widely farmed shellfish worldwide. As the primary shellfish species cultivated in B.C., it has an estimated value of $16 million in 2023. However, they are increasingly affected by mass-mortality events of unknown cause. In 2020, researchers collected 33 oysters from two farms in B.C. and 26 wild oysters from 10 nearby sites. PONV1 was detected in 20 of the dead or dying farmed oysters but was absent in healthy wild oysters, indicating a strong link between the virus and oyster mortality. By interrogating global genetic databases, researchers also found close relatives of PONV1 in Pacific oysters from Europe and Asia, indicating that this group of viruses are globally widespread.

Kevin (Xu) Zhong. Credit: Zhe Cai

Most RNA viruses have small genomes, typically below 30 kb, but PONV1 has a genome size of 64 kb. “The enormous genome of this virus makes it particularly fascinating as it pushes the known boundaries of how big RNA virus genomes can get,” said Dr. Zhong, first author of the study and Research Associate at the Department of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences (EOAS) at UBC. “A larger genome may allow the virus to encode more genes or protein domains, potentially expanding or enhancing its ability to interact with hosts. This discovery offers a rare window into the possible evolutionary mechanisms that enable genome expansion in RNA viruses.”

Collecting oysters in a pot. Credit: Amy M. Chan

Farmed oysters with PONV1. Credit: Amy M. Chan

PONV1 and its relatives appear to infect only oysters, so humans are not at risk from contracting the virus, said Dr. Suttle, senior author and Professor at EOAS. “This research is not a cause for alarm. Rather, this is a meaningful step forward in advancing our understanding of oyster health and supporting the long-term sustainability of shellfish aquaculture.”

Curtis Suttle looking at water samples. Credit: Amy M. Chan

Amy Chan (Research Scientist, Suttle Lab) sampling an oyster bed. Credit: Kristi Miller-Saunders

Watch our interview with Dr. Zhong about this discovery:

You can also watch or listen to interviews with Dr. Suttle and Dr. Zhong on CBC On the Coast, Global News, CKNW Jill Bennett Show, Fairchild TV (新時代電視), Cortes Currents.

Read more about this discovery on Scienmag, Earth.com, National Fisherman, and Glacier Media (via North Shore News, Richmond News, Vancouver is Awesome, Pique NewsMagazine, Times Colonist, Squamish Chief, Business in Vancouver (BIV), Bowen Island Undercurrent, Powell River Peak, and Sechelt / Gibsons Coast Reporter).

Follow more news releases about this discovery here: Evolutionarily divergent nidovirus with an exceptionally large genome identified in Pacific oysters undergoing mass mortality

Microbial DNA offers clues to where copper is buried

Read the UBC Science article here: Bacterial fingerprints in soil show where copper is buried

Copper is vital to various industries, including manufacturing, construction and transportation, and Canada holds nearly 900 million tonnes of copper. According to a recent study in Geology, researchers from UBC departments of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences (EOAS), Microbiology and Immunology (MBIM), and Mineral Deposit Research Unit (MDRU) have developed a new technique to detect buried copper deposits using microbial DNA in the surface soil as ‘biological fingerprints’.

The team introduced copper to soil microbes from two locations in Canada – tundra from the Northwest Territories and a known porphyry copper deposit in Deerhorn, B.C—and looked at shifts in microbial composition and abundance through DNA sequencing.

“We took those changed communities of microbes as indicators for the presence of copper—essentially a biological fingerprint made up of many individual species,” said first author and Ph.D. Candidate Bianca Iulianella Phillips. “We then analyzed the soil from Deerhorn, and found that from that fingerprint, 29 species of microbes are present above the mineral deposit. This demonstrates that there is a predictive capability with our technique, showing where copper deposits are buried.”

“Our approach offers a new dimension to mineral exploration—enhancing discovery success and helping reduce costs with more precise targeting,” said senior author Dr. Sean Crowe, professor in UBC EOAS and MBIM. “As the industry adopts this approach more broadly, not only will it become more cost-effective and accessible, but the increasing volume of data will also make the technique more robust, accelerating learning and refinement.”

Read about previous work of the team in detecting kimberlite, diamond-containing rocks: Biological fingerprints in soil show where diamond-containing ore is buried

PCIGR at Goldschmidt 2025

Last week, researchers from the Pacific Centre for Isotopic and Geochemical Research (PCIGR) showcased their work at the Goldschmidt Conference, the premiere international meeting on geochemistry.

This year’s conference featured a special session in honor of Dr. Dominique Weis (Director of PCIGR, Professor at UBC EOAS) and Dr. Catherine Chauvel (Research Director of the Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris) in recognition of their groundbreaking contributions to mantle geochemistry.

Dr. Weis was also interviewed by the European Association of Geochemistry during the event, where she reflected on receiving this honor and her insights on the future of mantle geochemistry. Read the blog here: What do we know about the composition of the mantle (Part 1)? An Interview with Dominique Weis

Ahead of the conference, PCIGR was invited by Targeted Films to produce a behind-the-scenes video highlighting the cutting-edge research and facilities at the center and in partnership with the Mineral Deposit Research Unit (MDRU) at UBC. Watch the video below and stay tuned for more content to come!

Read more here:

PCIGR at Goldschmidt 2025!