News

Stay up-to-date with what's happening in EOAS

Early Mars was covered in ice sheets, not flowing rivers

Anna Grau Galofre, Mark Jellinek, and Gordon 'Oz' Osinski

A large number of the valley networks scarring Mars’s surface were carved by water melting beneath glacial ice, not by free-flowing rivers as previously thought, according to new UBC research published today in Nature Geoscience. The findings effectively throw cold water on the dominant “warm and wet ancient Mars” hypothesis, which postulates that rivers, rainfall and oceans once existed on the red planet.

To reach this conclusion, lead author Anna Grau Galofre, former PhD student in the Department of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences, developed and used new techniques to examine thousands of Martian valleys. She and her co-authors also compared the Martian valleys to the subglacial channels in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago and uncovered striking similarities.

“For the last 40 years, since Mars’s valleys were first discovered, the assumption was that rivers once flowed on Mars, eroding and originating all of these valleys,” says Grau Galofre. “But there are hundreds of valleys on Mars, and they look very different from each other. If you look at Earth from a satellite you see a lot of valleys: some of them made by rivers, some made by glaciers, some made by other processes, and each type has a distinctive shape. Mars is similar, in that valleys look very different from each other, suggesting that many processes were at play to carve them.”

The similarity between many Martian valleys and the subglacial channels on Devon Island in the Canadian Arctic motivated the authors to conduct their comparative study. “Devon Island is one of the best analogues we have for Mars here on Earth—it is a cold, dry, polar desert, and the glaciation is largely cold-based,” says co-author Gordon Osinski, professor in Western University’s Department of Earth Sciences and Institute for Earth and Space Exploration.

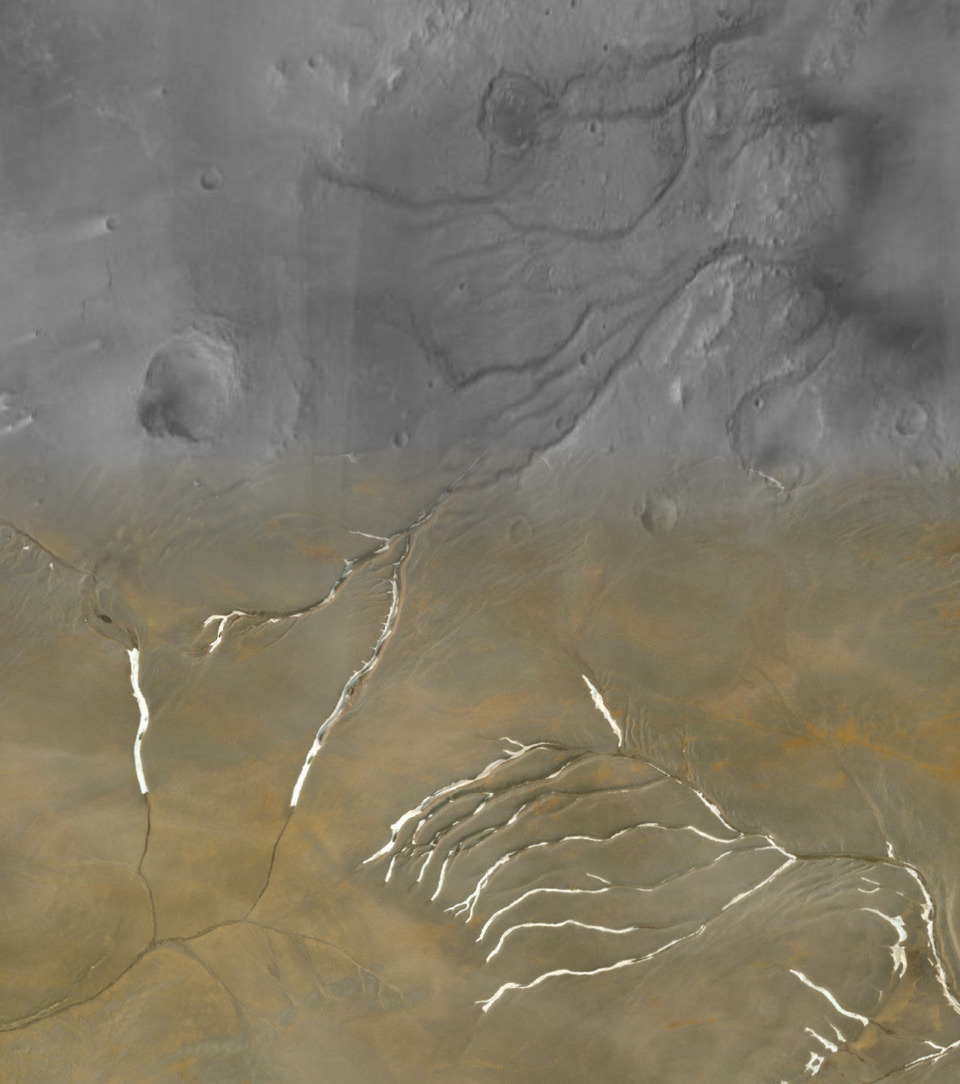

Collage showing Mars’s Maumee valleys (top half) superimposed with channels on Devon Island in Nunavut (bottom half). The shape of the channels, as well as the overall network, appears almost identical. Credit: Cal-Tech CTX mosaic and MAXAR/Esri.

In total, the researchers analyzed more than 10,000 Martian valleys, using a novel algorithm to infer their underlying erosion processes. “These results are the first evidence for extensive subglacial erosion driven by channelized meltwater drainage beneath an ancient ice sheet on Mars,” says co-author Mark Jellinek, professor in UBC’s department of earth, ocean and atmospheric sciences. “The findings demonstrate that only a fraction of valley networks match patterns typical of surface water erosion, which is in marked contrast to the conventional view. Using the geomorphology of Mars’ surface to rigorously reconstruct the character and evolution of the planet in a statistically meaningful way is, frankly, revolutionary.”

Grau Galofre’s theory also helps explain how the valleys would have formed 3.8 billion years ago on a planet that is further away from the sun than Earth, during a time when the sun was less intense. “Climate modelling predicts that Mars’ ancient climate was much cooler during the time of valley network formation,” says Grau Galofre, currently a SESE Exploration Post-doctoral Fellow at Arizona State University. “We tried to put everything together and bring up a hypothesis that hadn’t really been considered: that channels and valleys networks can form under ice sheets, as part of the drainage system that forms naturally under an ice sheet when there’s water accumulated at the base.”

These environments would also support better survival conditions for possible ancient life on Mars. A sheet of ice would lend more protection and stability of underlying water, as well as providing shelter from solar radiation in the absence of a magnetic field—something Mars once had, but which disappeared billions of years ago.

While Grau Galofre’s research was focused on Mars, the analytical tools she developed for this work can be applied to uncover more about the early history of our own planet. Jellinek says he intends to use these new algorithms to analyze and explore erosion features left over from very early Earth history.

“Currently we can reconstruct rigorously the history of global glaciation on Earth going back about a million to five million years,” says Jellinek. “Anna’s work will enable us to explore the advance and retreat of ice sheets back to at least 35 million years ago—to the beginnings of Antarctica, or earlier—back in time well before the age of our oldest ice cores. These are very elegant analytical tools.”

Empirical mass flow runout analysis: Innovative new tools

Negar Ghahramani, Andrew Mitchell, and Scott McDougall

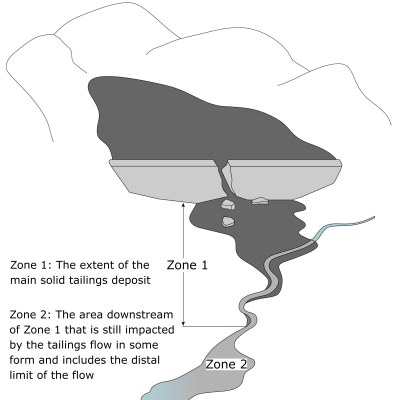

Mass flows of geological materials can travel substantial distances, causing significant loss of life, environmental damage, and economic costs. The Geohazards Research Team within the Geological Engineering program studies a variety of these phenomena, including natural events like rock avalanches and debris flows, and human-related events such as flows resulting from tailings dam breaches. The hazards from these events are largely related to their mobility, how far they travel and how much they spread, which can be quite uncertain. Case studies of real events are key to developing better empirical methods, either based on physical scaling laws, statistical relationships, or a combination of both, to estimate the extent of potential flows. The first stage of both of these pieces of work was to develop consistent definitions and criteria for describing and mapping the case studies. Empirical relationships for both tailings flows and rock avalanches were developed using the new databases which can be used both in academia for future studies and in industry for practical application to risk management problems. This work show the potential for applying similar methods to a wide variety of flow-like processes.

“Viruses and nutrient cycles in the sea” is honored with the John H. Martin Award by ASLO

“Viruses and nutrient cycles in the sea”, 1999, by Drs. Steven Wilhelm (University of Tennessee) and Curtis Suttle (University of British Columbia) recently received the 2021 John H. Martin Award presented by the Association for the Sciences of Limnology and Oceanography (ASLO). This award is given to one paper each year that has led to fundamental shifts in research focus and interpretation of a large body of previous observations. The award will be presented at the 2021 ASLO Aquatic Sciences Virtual Meeting in June.

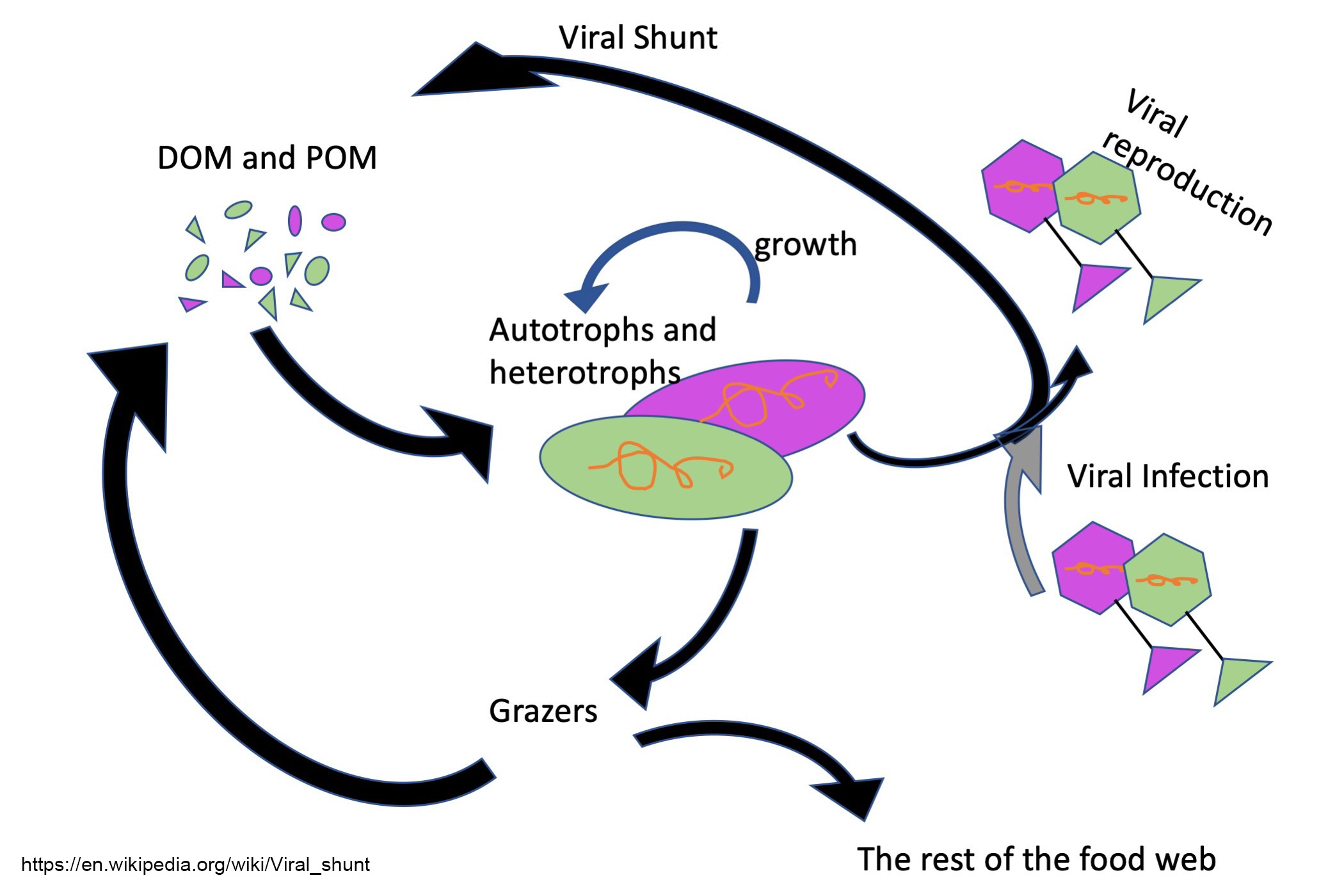

The foundational 1999 paper, conceived while Wilhelm was a postdoctoral associate in the Suttle lab, originated the concept of the ‘viral shunt,’ the phenomenon in which viral infection of marine microbes redirects organic carbon flow away from higher tropic levels and through the microbial loop. Drawing on early estimates of viral production in the water column, Wilhelm and Suttle shined a light on the considerable role viruses play in ocean biogeochemical cycles at a time when much of the research was focused on describing viral diversity and distribution. Their calculations showed that a staggering 25% of all photosynthetically fixed carbon, and associated nutrients, in the ocean may be recycled through the viral shunt. Additionally, Wilhelm and Suttle made some of the first estimates of the total carbon stored in the viral pool and made eye-opening comparisons to the carbon stored in other types of marine organisms (including whales). Today, the concept of the viral shunt continues to influence our understanding of ocean ecosystem functioning and nutrient cycles. With >1000 citations, and more than 300 in the last five years, the legacy of “Viruses and nutrient cycles in the sea” and the viral shunt concept is still strongly felt in the field today.

“Every so often a novel concept is described which truly transforms a scientific field for decades,” says ASLO President Roxane Maranger. “Wilhelm and Suttle’s concept of the ‘viral shunt’ as a major pathway of oceanic carbon flow in their 1999 paper is a stunning example of such a transformation.”

“Every so often a novel concept is described which truly transforms a scientific field for decades,” says ASLO President Roxane Maranger. “Wilhelm and Suttle’s concept of the ‘viral shunt’ as a major pathway of oceanic carbon flow in their 1999 paper is a stunning example of such a transformation.”

Full Citation: Wilhelm, S.W. and C.A. Suttle. 1999. Viruses and nutrient cycles in the sea, BioScience 49(10): 781-788. doi.org/10.2307/1313569.

Quarantine Conversation with Prof. Rachel White

Rachel is an Assistant Professor in Climate Dynamics in the EOAS Department. She studied physics at the University of Cambridge, before completing her PhD in Atmospheric Physics at Imperial College London. She has recently moved to Vancouver after working as a post-doc in Seattle (US) and then Barcelona (Spain), and is excited to be here at UBC. Rachel enjoys climate outreach and talking to the public about climate and extreme weather, and has aspirations to one day combine her hobby of aerial circus with a climate outreach event!

From modest digs at UBC, Canadian Earth science journal celebrates 100 years

The Canadian Mineralogist, a peer-reviewed scientific journal that publishes papers from worldwide authors on all aspects of mineralogy, crystallography, petrology, geochemistry and mineral deposits, celebrates its 100th anniversary this year.

In typical Canadian fashion, the journal operates on a shoestring compared to its rivals—its office is a back room in UBC’s LS Klinck building and its editorial is powered by volunteers.

“This is one of very few scientific journals that isn’t associated with a commercial publishing house,” says UBC earth scientist Dr. Lee Groat, who serves as part-time chief editor of the journal. “Given increasing competition from commercial and predatory journals it’s unknown how long Canadian Mineralogist can survive in its current form. For now, however, we’re celebrating 100 years of a very unique Canadian achievement.”

Dr. Groat and managing editor Mackenzie Parker (UBC Earth and Ocean Sciences 2001) are aided by volunteer editors from across Canada and eight other countries. EOAS students gain experience and play an important paid role in fact checking—for example ensuring that mineral names adhere to international standards.

Rhiana Henry, the current mineral fact checker for Canadian Mineralogist and PhD student at UBC Vancouver, says working on the journal helps broaden her horizons beyond topics that would be covered under her PhD.

“Mineralogy bridges the disciplines of geology, crystallography, petrology, mineral deposits, and geochemistry, and I’m learning about each field,” says Henry, whose PhD is focused on a single mineral, beryl.

“I’ve read papers ranging from description of crystal growth in caves due to bat guano, papers about platinum group element ores in South Africa, papers on in-depth crystallography of newly described minerals, gem turquoise from the Middle East, minerals created by lightning strikes, and of the mineralogy and petrology of pegmatites from around the world.”

The ragtag approach does seem to be working—in 2019 the journal ranked second in Canada in its field, with an impact factor of 74.

The Canadian Mineralogist has its roots in Contributions to Canadian Mineralogy (part of the University of Toronto Studies, Geological Series), which was founded in 1921 by Thomas Leonard Walker and was the leading publication of academic mineralogical research in Canada for many years.

Support for Studies was withdrawn in 1948, but Martin Peacock, who at the time was both responsible for editing Contributions and serving as president of the Mineralogical Society of America, persuaded his council to devote one of the six yearly numbers of American Mineralogist to Canadian papers (they were called Canadian Contributions). Canadian Contributions continued as part of American Mineralogist until 1955, with The Canadian Mineralogist coming into existence two years later, in 1957.

The Canadian Mineralogist is recognized to be the continuation of the earlier Contributions, and its volumes are numbered accordingly. The Contributions to Canadian Mineralogy, University of Toronto Studies have been designated as volumes l to 4 of The Canadian Mineralogist; the seven Contributions of American Mineralogist have been designated as volume 5; and thus the first volume published as The Canadian Mineralogist is volume 6.

Currently six issues totaling approximately 120 papers are published per year.

A Day in the Life - Johan Gilchrist

Check out a day in the life of Johan Gilchrist, an experimental volcanologist and PhD Candidate at EOAS.