News

Stay up-to-date with what's happening in EOAS

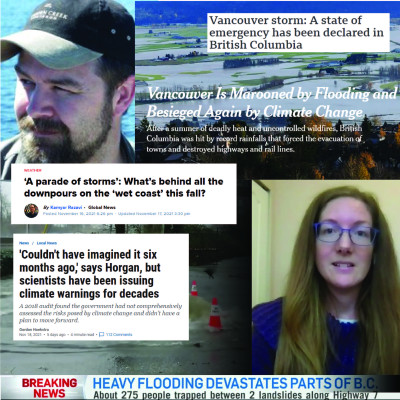

EOAS Faculty Provide Insight on Extreme Downpours and Landslides

EOAS faculty members Brett Gilley and Dr. Rachel White have been valuable contacts for national and global news outlets reporting on the damage wreaked by the record-breaking BC rainfall last week.

Last week's storm, following on the heels of multiple sustained heavy rainfalls in early November, was delivered by an atmospheric river – a long strip of moisture that rapidly transports water from warmer areas towards the poles. BC has experienced an unusual amount of atmospheric river events this season, as Dr. White, a researcher of large-scale atmospheric dynamics, explains in an interview with CTV News. In other interviews with the BBC and The New York Times, she stresses that global warming has made atmospheric rivers, and the natural disasters they cause, more and more common. "As we warm up the atmosphere, as we warm up the oceans - more water is evaporated…essentially the atmosphere can carry more water towards our mountains."

This water – delivering the equivalent of the region’s monthly rainfall in just over 24 hours – caused flooding and landslides that sent the British Columbia government into a state of emergency.

As Associate Professor and natural disaster specialist Brett Gilley explained to Global News during a recent interview, other fallouts of global warming have a compounding effect on landslides triggered by the rainfall. BC’s heavy forest fire season weakened soil, while this past summer’s intense heat dome weakened tree roots that play a crucial role in slope stability. Already a landslide-prone province due to its mountainous nature, huge volumes of precipitation sent many of these compromised slopes crashing down onto BC’s highways and bridges.

CKNW’s Jas Johal interviewed Gilley on how to protect infrastructure from future landslides – often a balancing act of targeting problematic areas using limited resources. As he describes to the Vancouver Sun, applying these protective measures can be complicated by matters of funding and policy. Despite this, he sees replacing buried roads and washed-away bridges as an opportunity to build infrastructure better equipped for a future where a changing climate will make natural disasters more common.

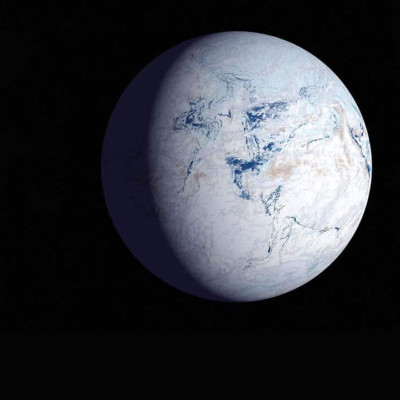

Earth's Plate Tectonic Climate Control

Mark Jellinek, Adrian Lenardic and Raymond T. Pierrehumbert

One of the most astonishing chapters in Earth’s history is “Snowball Earth”: The twice entombing of the whole planet beneath a kilometer-thick layer of ice for tens of millions of years. More improbable still is that the end of the last episode around 635 million years ago somehow helped to spark the rise of the diversity of complex animals and land plants along with the high atmospheric oxygen levels that define the modern world. Surprises were not, however, limited to the biosphere. Through the snowball episodes, Earth’s average global climate switched sharply in character from a relatively warm and ice-free world of the previous billion years (the boring billion) to one akin to present day, marked by glacial cycles, dynamic ice sheets and profound climate variability of varying intensity over time scales ranging from years to millions of years. How did Earth’s climate become so cold after being warm for so long? Why did consequent global glaciations persist for tens of millions of years and why were there two episodes? What triggered snowball Earth in the first place and how did Earth eventually escape this climatic death sentence? Why is Earth’s current climate so nervous—so sensitive to, for example, anthropogenic sources of CO2. In work that develops a new view of the dynamics of “the Earth System”, we show how effects of plate tectonics on Earth’s mantle convective stirring, including the intermittent formation and fragmentation of supercontinents, modulates the major volcanic and weathering controls on Earth’s average climate, setting the stage for protracted periods of warmth, for variability akin to present day and for snowball Earth.

Uncovering the subsurface by merging physics and geology with data science: A diamond exploration study

Thibault Astic, Dominique Fournier, and Doug Oldenburg

The DO-27 kimberlite pipe is a geologic structure located in the Northwest Territories, Canada. Two known kimberlite facies are found within the pipe: one is diamondiferous and characterized by a low-density while the other is magnetic but sterile. They respectively produce gravity and magnetic anomalies that can be measured remotely and used to image the subsurface and map underground resources through a mathematical process called inversion. When multiple surveys with different physics are collected over the same area, combining them in a coherent interpretation can be complicated by apparent inconsistencies between the inversion results from each method due to the lack of integration. Our novel inversion framework, which merges physics simulation with data science, overcomes those issues by performing multi-physics analysis that incorporates petrophysical and geological information, thus making a step forward bridging geology and geophysics. By jointly analyzing the gravity and magnetic responses produced remotely by the pipe, We improved the delineation of the 3-D subsurface structures of the two known kimberlite facies and located a third previously unidentified facies. Those new tools are highly flexible, making them suitable for many problems related to estimating the resources available for a sustainable future, such as minerals, water, and carbon sequestration capacity.

Day(s) in the Life - Yayla Sezginer and Katrina Schuler

Join UBC Oceanography graduate students Yayla Sezginer and Katrina Schuler for a second of every day during their recent research cruise in the Arctic.

Meet Shandin Pete - Hydrogeologist and Science Educator

Dr. Shandin Pete was raised in Nłq̓alqʷ (“Place of the thick trees”, Arlee, Montana). His mother is from the Bitterroot Band of Salish in Montana and his father is Diné from Beshbihtoh Valley in Arizona. He is a hydrogeologist and science educator with interest in Indigenous research methodologies, geoscientific ethnography, Indigenous astronomy, social-political tribal structures, culturally congruent instructional strategies, and indigenous science philosophies. Most of his work in recent years has focused on community engagement to understanding shifts in an Indigenous paradigm of research for science knowledge production. This work has included extensive collaboration with tribal knowledge holders across Native communities and Indigenous academic scholars at institutions nationally and internationally.

Meet Maite Maldonado - Oceanographer

Maite is an oceanographer who specializes in marine phytoplankton and the role that natural & human-produced trace metals play in their population levels. Phytoplankton may be microscopic, but on an annual basis, they convert around 45 gigatons of carbon dioxide to organic carbon, which is roughly half the total carbon fixation on the planet! She also studies how much of that converted carbon then sinks into the deep ocean (and how that sinking process happens). However, not all parts of the Earth’s oceans are equally vibrant with microbial life. Maite has studied which areas are more productive, and why, putting her on the front lines of our understanding of climate change.